Documentary film

Nanook of the North (1922)

Contents

Humphrey Jennings on the set of Family Portrait 1950

Definition

Bolesław Matuszewski book Une nouvelle source de l’histoire 1898 frontispiece

Boleslaw Matuszewski

The cover of Bolesław Matuszewski book Une nouvelle source de l’histoire. (A New Source of History) from 1898 the first publication about documentary function of cinematography.

Polish writer and filmmaker Bolesław Matuszewski was among those who identified the mode of documentary film. He wrote two of the earliest texts on cinema Une nouvelle source de l’histoire (eng. A New Source of History) and La photographie animée (eng. Animated photography). Both were published in 1898 in French and among the early written works to consider the historical and documentary value of the film.[3] Matuszewski is also among the first filmmakers to propose the creation of a Film Archive to collect and keep safe visual materials.[4]

John Grierson

Moana (1926)

In popular myth, the word documentary was coined by Scottish documentary filmmaker John Grierson in his review of Robert Flaherty‘s film Moana (1926), published in the New York Sun on 8 February 1926, written by “The Moviegoer” (a pen name for Grierson).[5]

Grierson’s principles of documentary were that cinema’s potential for observing life could be exploited in a new art form; that the “original” actor and “original” scene are better guides than their fiction counterparts to interpreting the modern world; and that materials “thus taken from the raw” can be more real than the acted article. In this regard, Grierson’s definition of documentary as “creative treatment of actuality”[6] has gained some acceptance, with this position at variance with Soviet film-maker Dziga Vertov‘s provocation to present “life as it is” (that is, life filmed surreptitiously) and “life caught unawares” (life provoked or surprised by the camera).

Dziga Vertov

Dziga Vertov – Kino Glaz (1924)

The American film critic Pare Lorentz defines a documentary film as “a factual film which is dramatic.”[7] Others further state that a documentary stands out from the other types of non-fiction films for providing an opinion, and a specific message, along with the facts it presents.[8]

Documentary practice is the complex process of creating documentary projects. It refers to what people do with media devices, content, form, and production strategies in order to address the creative, ethical, and conceptual problems and choices that arise as they make documentaries.

Documentary filmmaking can be used as a form of journalism, advocacy, or personal expression.

Man With A Movie Camera (1929)

History

Auguste and Louis Lumiere – Factory Workers Leaving Work (1896)

Auguste and Louis Lumiere – Factory Workers Leaving Work (1896)

Pre–1900

Early film (pre-1900) was dominated by the novelty of showing an event. They were single-shot moments captured on film: a train entering a station, a boat docking, or factory workers leaving work. These short films were called “actuality” films; the term “documentary” was not coined until 1926. Many of the first films, such as those made by Auguste and Louis Lumière, were a minute or less in length, due to technological limitations.

Films showing many people (for example, leaving a factory) were often made for commercial reasons: the people being filmed were eager to see, for payment, the film showing them. One notable film clocked in at over an hour and a half, The Corbett-Fitzsimmons Fight. Using pioneering film-looping technology, Enoch J. Rector presented the entirety of a famous 1897 prize-fight on cinema screens across the United States.

The Corbett – Fitzsimmons Fight – Film Poster (1897)

The Corbett – Fitzsimmons Fight (1897)

In May 1896, Bolesław Matuszewski recorded on film few surigical operations in Warsaw and Saint Petersburg hospitals. In 1898, French surgeon Eugène-Louis Doyen invited Bolesław Matuszewski and Clément Maurice and proposed them to recorded his surigical operations. They started in Paris a series of surgical films sometime before July 1898.[9] Until 1906, the year of his last film, Doyen recorded more than 60 operations. Doyen said that his first films taught him how to correct professional errors he had been unaware of. For scientific purposes, after 1906, Doyen combined 15 of his films into three compilations, two of which survive, the six-film series Extirpation des tumeurs encapsulées (1906), and the four-film Les Opérations sur la cavité crânienne (1911). These and five other of Doyen’s films survive.[10]

Between July 1898 and 1901, the Romanian professor Gheorghe Marinescu made several science films in his neurology clinic in Bucharest:[11]Walking Troubles of Organic Hemiplegy (1898), The Walking Troubles of Organic Paraplegies (1899), A Case of Hysteric Hemiplegy Healed Through Hypnosis (1899), The Walking Troubles of Progressive Locomotion Ataxy (1900), and Illnesses of the Muscles (1901). All these short films have been preserved. The professor called his works “studies with the help of the cinematograph,” and published the results, along with several consecutive frames, in issues of “La Semaine Médicale” magazine from Paris, between 1899 and 1902.[12]

Gheorghe Marinescu

In 1924, Auguste Lumiere recognized the merits of Marinescu’s science films: “I’ve seen your scientific reports about the usage of the cinematograph in studies of nervous illnesses, when I was still receiving “La Semaine Médicale,” but back then I had other concerns, which left me no spare time to begin biological studies. I must say I forgot those works and I am thankful to you that you reminded them to me. Unfortunately, not many scientists have followed your way.”[13][14][15]

1900–1920

Travelogue films were very popular in the early part of the 20th century. They were often referred to by distributors as “scenics.” Scenics were among the most popular sort of films at the time.[16] An important early film to move beyond the concept of the scenic was In the Land of the Head Hunters (1914), which embraced primitivism and exoticism in a staged story presented as truthful re-enactments of the life of Native Americans.

Contemplation is a separate area. Pathé is the best-known global manufacturer of such films of the early 20th century. A vivid example is Moscow clad in snow (1909).

Moscow Clad in Snow (1909)

Biographical documentaries appeared during this time, such as the feature Eminescu-Veronica-Creangă (1914) on the relationship between the writers Mihai Eminescu, Veronica Micle and Ion Creangă (all deceased at the time of the production) released by the Bucharest chapter of Pathé.

Early color motion picture processes such as Kinemacolor—known for the feature With Our King and Queen Through India (1912)—and Prizmacolor—known for Everywhere With Prizma (1919) and the five-reel feature Bali the Unknown (1921)—used travelogues to promote the new color processes. In contrast, Technicolor concentrated primarily on getting their process adopted by Hollywood studios for fictional feature films.

With Our King and Queen Through India (1912)

Kinemacolor Poster (1912)

Also during this period, Frank Hurley‘s feature documentary film, South (1919), about the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition was released. The film documented the failed Antarctic expedition led by Ernest Shackleton in 1914.

Frank Hurley’s South (1914)

1920s

Romanticism

Nanook of the North (1922)

With Robert J. Flaherty‘s Nanook of the North in 1922, documentary film embraced romanticism; Flaherty filmed a number of heavily staged romantic films during this time period, often showing how his subjects would have lived 100 years earlier and not how they lived right then. For instance, in Nanook of the North, Flaherty did not allow his subjects to shoot a walrus with a nearby shotgun, but had them use a harpoon instead. Some of Flaherty’s staging, such as building a roofless igloo for interior shots, was done to accommodate the filming technology of the time.

Grass (1925)

Paramount Pictures tried to repeat the success of Flaherty’s Nanook and Moana with two romanticized documentaries, Grass (1925) and Chang (1927), both directed by Merian Cooper and Ernest Schoedsack.

On the set of Chang (1927)

Chang ( 1927)

Chang (1927) Poster

The city symphony

City Symphony Films were avant-garde films made during the 1920s to 1930s. These films were particularly influenced by modern art: namely Cubism, Constructivism, and Impressionism. (See A.L Rees, 2011)[17] According to Scott Macdonald (2010), city symphony film can be located as an intersection between documentary and avant-garde film; “avant-doc”. However, A.L. Rees suggest to see them as avant-garde films. (Rees, 2011: 35)

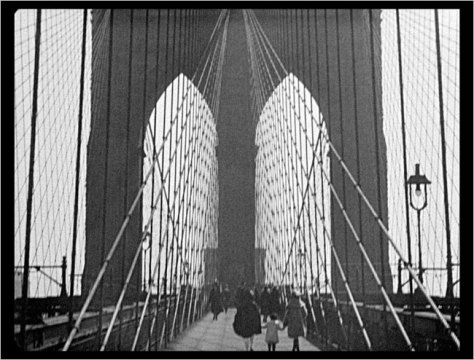

Manhatta (1921)

Manhatta (1921)

City Symphony films include Manhatta (dir. Paul Strand, 1921), Paris Nothing but the Hours (dir. Alberto Cavalcanti, 1926), Twenty Four Dollar Island (dir. Robert Flaherty, 1927), Études sur Paris (dir. André Sauvage, 1928), The Bridge (1928), and Rain (1929), both by Joris Ivens.

Paris Nothing But Hours (1926) – Alberto Cavalcanti

Twenty-Four Dollar Island (1927) – Robert Flaherty

Bridge (1928) – Joris Ivens

Rain (1929) – Joris Ivens

But the most famous city symphony films are Berlin, Symphony of a Great City (dir. Walter Ruttman, 1927) and The Man with a Movie Camera (dir. Dziga Vertov, 1929).

Berlin, Symphony of a Great City (1927) – Walter Ruttman

Berlin, Symphony of a Great City (1927) – Walter Ruttman – Film Poster

Walter Ruttmann’s Berlin, Symphony of a Great City (1927), is shot and edited like a visual-poem.

A City Symphony Film, as the name suggests, is usually based around a major metropolitan city area and seek to capture the lives, events and activities of the city.

It can be abstract and cinematographic (see Walter Ruttmann’s Berlin) or utilise Russian Montage theory (See Dziga Vertov’s Man with the Movie Camera). But most importantly, a city symphony film is like a cine-poem and is shot and edited like a “symphony”.

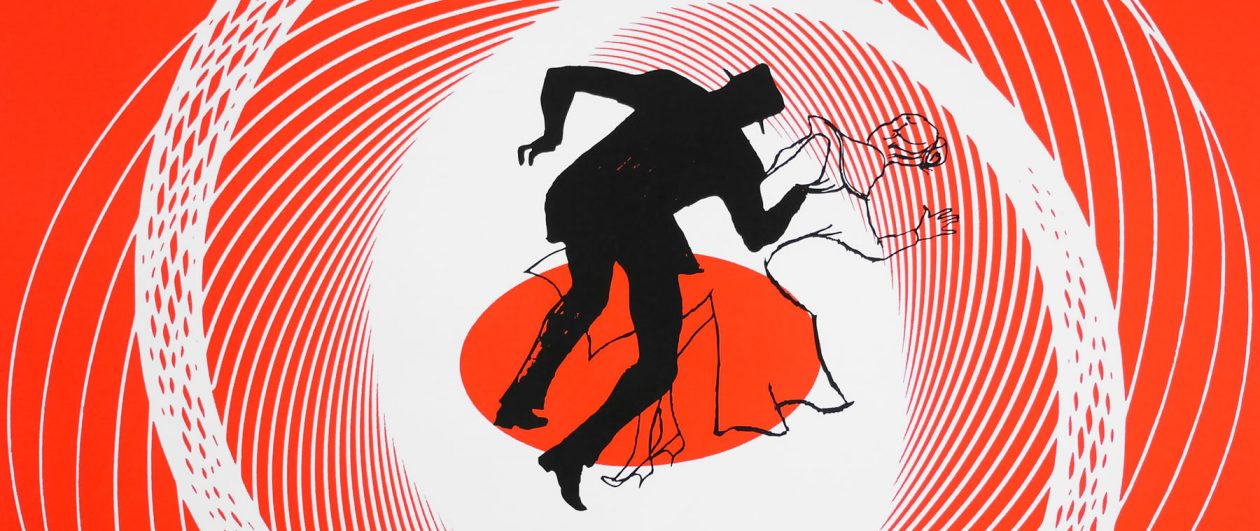

Man With A Movie Camera (1929)

The continental, or realist, tradition focused on humans within human-made environments, and included the so-called “city symphony” films such as Walter Ruttmann‘s Berlin, Symphony of a City (of which Grierson noted in an article[18] that Berlin represented what a documentary should not be), Alberto Cavalcanti‘s Rien que les heures, and Dziga Vertov‘s Man with the Movie Camera. These films tend to feature people as products of their environment, and lean towards the avant-garde.

Kino Pravda (1925) – Dziga Vertov

Kino-Pravda

Dziga Vertov was central to the SovietKino-Pravda (literally, “cinematic truth”) newsreel series of the 1920s. Vertov believed the camera—with its varied lenses, shot-counter shot editing, time-lapse, ability to slow motion, stop motion and fast-motion—could render reality more accurately than the human eye, and made a film philosophy out of it.

Kino Pravda (1922)

Newsreel tradition

The newsreel tradition is important in documentary film; newsreels were also sometimes staged but were usually re-enactments of events that had already happened, not attempts to steer events as they were in the process of happening. For instance, much of the battle footage from the early 20th century was staged; the cameramen would usually arrive on site after a major battle and re-enact scenes to film them.

British Pathe Newsreel

1920s–1940s

The propagandist tradition consists of films made with the explicit purpose of persuading an audience of a point. One of the most celebrated and controversial propaganda films is Leni Riefenstahl‘s film Triumph of the Will (1935), which chronicled the 1934 Nazi Party Congress and was commissioned by Adolf Hitler. Leftist filmmakers Joris Ivens and Henri Storck directed Borinage (1931) about the Belgian coal mining region. Luis Buñuel directed a “surrealist” documentary Las Hurdes (1933).

Leni Riefenstahl filming Triumph of the Will (1935)

Borinage (1934) – Joris Ivens

Las Hurdes (1933) – Luis Bunuel

Pare Lorentz‘s The Plow That Broke the Plains (1936) and The River (1938) and Willard Van Dyke‘s The City (1939) are notable New Deal productions, each presenting complex combinations of social and ecological awareness, government propaganda, and leftist viewpoints. Frank Capra‘s Why We Fight (1942–1944) series was a newsreel series in the United States, commissioned by the government to convince the U.S. public that it was time to go to war. Constance Bennett and her husband Henri de la Falaise produced two feature-length documentaries, Legong: Dance of the Virgins (1935) filmed in Bali, and Kilou the Killer Tiger (1936) filmed in Indochina.

The Plow That Broke The Plains (1936)

The City (1939)

Legong (1935)

Frank Capra and John Ford – Why We Fight (1942-1944)

In Canada, the Film Board, set up by John Grierson, was created for the same propaganda reasons. It also created newsreels that were seen by their national governments as legitimate counter-propaganda to the psychological warfare of Nazi Germany (orchestrated by Joseph Goebbels).

Conference of “World Union of documentary films” in 1948 Warsaw featured famous directors of the era: Basil Wright (on the left), Elmar Klos, Joris Ivens (2nd from the right), and Jerzy Toeplitz.

In Britain, a number of different filmmakers came together under John Grierson. They became known as the Documentary Film Movement.

Grierson, Alberto Cavalcanti, Harry Watt, Basil Wright, and Humphrey Jennings amongst others succeeded in blending propaganda, information, and education with a more poetic aesthetic approach to documentary. Examples of their work include Drifters (John Grierson), Song of Ceylon (Basil Wright), Fires Were Started, and A Diary for Timothy (Humphrey Jennings). Their work involved poets such as W. H. Auden, composers such as Benjamin Britten, and writers such as J. B. Priestley. Among the best known films of the movement are Night Mail and Coal Face.

Alberto Cavalcanti

Harry Watt

Basil Wright

Humphrey Jennings

Night Mail (1935)

A Diary For Timothy (1945)

1950s–1970s

Cinéma-vérité

Cinéma vérité (or the closely related direct cinema) was dependent on some technical advances in order to exist: light, quiet and reliable cameras, and portable sync sound.

Cinéma vérité and similar documentary traditions can thus be seen, in a broader perspective, as a reaction against studio-based film production constraints. Shooting on location, with smaller crews, would also happen in the French New Wave, the filmmakers taking advantage of advances in technology allowing smaller, handheld cameras and synchronized sound to film events on location as they unfolded.

French New Wave

Although the terms are sometimes used interchangeably, there are important differences between cinéma vérité (Jean Rouch) and the North American “Direct Cinema” (or more accurately “Cinéma direct“), pioneered by, among others, Canadians Allan King, Michel Brault, and Pierre Perrault,[citation needed] and Americans Robert Drew, Richard Leacock, Frederick Wiseman, and Albert and David Maysles.

Jean Rouche

Alan King

Richard Leacock

Albert Maysles

Frederick Wiseman

The directors of the movement take different viewpoints on their degree of involvement with their subjects. Kopple and Pennebaker, for instance, choose non-involvement (or at least no overt involvement), and Perrault, Rouch, Koenig, and Kroitor favor direct involvement or even provocation when they deem it necessary.

Barbara Kopple

D A Pennebaker

The films Chronicle of a Summer (Jean Rouch), Dont Look Back (D. A. Pennebaker), Grey Gardens (Albert and David Maysles), Titicut Follies (Frederick Wiseman), Primary and Crisis: Behind a Presidential Commitment (both produced by Robert Drew), Harlan County, USA (directed by Barbara Kopple), Lonely Boy (Wolf Koenig and Roman Kroitor) are all frequently deemed cinéma vérité films.

The fundamentals of the style include following a person during a crisis with a moving, often handheld, camera to capture more personal reactions. There are no sit-down interviews, and the shooting ratio (the amount of film shot to the finished product) is very high, often reaching 80 to one. From there, editors find and sculpt the work into a film. The editors of the movement—such as Werner Nold, Charlotte Zwerin, Muffie Myers, Susan Froemke, and Ellen Hovde—are often overlooked, but their input to the films was so vital that they were often given co-director credits.

Famous cinéma vérité/direct cinema films include Les Raquetteurs,[19]Showman, Salesman, Near Death, and The Children Were Watching.

Chronicle of A Summer (1961)

Don’t Look Back (1967)

Grey Gardens (1975)

Titticut Follies (1967)

Harlan County USA (1975)

Political weapons

In the 1960s and 1970s, documentary film was often conceived as a political weapon against neocolonialism and capitalism in general, especially in Latin America, but also in a changing Quebec society. La Hora de los hornos (The Hour of the Furnaces, from 1968), directed by Octavio Getino and Arnold Vincent Kudales Sr., influenced a whole generation of filmmakers. Among the many political documentaries produced in the early 1970s was “Chile: A Special Report,” public television’s first in-depth expository look of the September 1973 overthrow of the Salvador Allende government in Chile by military leaders under Augusto Pinochet, produced by documentarians Ari Martinez and José Garcia.

The Hour of the Furnaces (1968)

Modern

Box office analysts have noted that this film genre has become increasingly successful in theatrical release with films such as Fahrenheit 9/11, Super Size Me, Food, Inc., Earth, March of the Penguins, Religulous, and An Inconvenient Truth among the most prominent examples. Compared to dramatic narrative films, documentaries typically have far lower budgets which makes them attractive to film companies because even a limited theatrical release can be highly profitable.

Fahrenheit 9/11 (2004)

An Inconvenient Truth (2006)

The nature of documentary films has expanded in the past 20 years from the cinema verité style introduced in the 1960s in which the use of portable camera and sound equipment allowed an intimate relationship between filmmaker and subject. The line blurs between documentary and narrative and some works are very personal, such as the late Marlon Riggs‘s Tongues Untied (1989) and Black Is…Black Ain’t (1995), which mix expressive, poetic, and rhetorical elements and stresses subjectivities rather than historical materials.[20]

Black is, black ain’t… (1995)

Historical documentaries, such as the landmark 14-hour Eyes on the Prize: America’s Civil Rights Years (1986—Part 1 and 1989—Part 2) by Henry Hampton, Four Little Girls (1997) by Spike Lee, and The Civil War by Ken Burns, UNESCO awarded independent film on slavery 500 Years Later, expressed not only a distinctive voice but also a perspective and point of views. Some films such as The Thin Blue Line by Errol Morris incorporated stylized re-enactments, and Michael Moore‘s Roger & Me placed far more interpretive control with the director. The commercial success of these documentaries may derive from this narrative shift in the documentary form, leading some critics to question whether such films can truly be called documentaries; critics sometimes refer to these works as “mondo films” or “docu-ganda.”[21] However, directorial manipulation of documentary subjects has been noted since the work of Flaherty, and may be endemic to the form due to problematic ontological foundations.

Four Little Girls (1997) – Spike Lee

The Civil War (1990) – Ken Burns

Thin Blue Line (1988) – Errol Morris

Documentary filmmakers are increasingly utilizing social impact campaigns with their films.[22] Social impact campaigns seek to leverage media projects by converting public awareness of social issues and causes into engagement and action, largely by offering the audience a way to get involved.[23] Examples of such documentaries include Kony 2012, Salam Neighbor, Gasland, Living on One Dollar, and Girl Rising.

Although documentaries are financially more viable with the increasing popularity of the genre and the advent of the DVD, funding for documentary film production remains elusive. Within the past decade, the largest exhibition opportunities have emerged from within the broadcast market, making filmmakers beholden to the tastes and influences of the broadcasters who have become their largest funding source.[24]

Modern documentaries have some overlap with television forms, with the development of “reality television” that occasionally verges on the documentary but more often veers to the fictional or staged. The making-of documentary shows how a movie or a computer game was produced. Usually made for promotional purposes, it is closer to an advertisement than a classic documentary.

Voices of Iraq (2004) – Kunert/Manes

Modern lightweight digital video cameras and computer-based editing have greatly aided documentary makers, as has the dramatic drop in equipment prices. The first film to take full advantage of this change was Martin Kunert and Eric Manes‘ Voices of Iraq, where 150 DV cameras were sent to Iraq during the war and passed out to Iraqis to record themselves.

National Geographic television collaborates local video production agencies to present the best content for viewers, APV delivered modern documentaries programming focussed on Hong Kong Local region with collaborating National Geographic.

Without words

Films in the documentary form without words have been made. From 1982, the Qatsi trilogy and the similar Baraka could be described as visual tone poems, with music related to the images, but no spoken content. Koyaanisqatsi (part of the Qatsi trilogy) consists primarily of slow motion and time-lapse photography of cities and many natural landscapes across the United States. Baraka tries to capture the great pulse of humanity as it flocks and swarms in daily activity and religious ceremonies.

Koyaanisqatsi (1982) – Godfrey Reggio

Bodysong was made in 2003 and won a British Independent Film Award for “Best British Documentary.”

The 2004 film Genesis shows animal and plant life in states of expansion, decay, sex, and death, with some, but little, narration.

Genesis (2004)

Narration styles

- Voice-over narrator

The traditional style for narration is to have a dedicated narrator read a script which is dubbed onto the audio track. The narrator never appears on camera and may not necessarily have knowledge of the subject matter or involvement in the writing of the script.

- Silent narration

This style of narration uses title screens to visually narrate the documentary. The screens are held for about 5–10 seconds to allow adequate time for the viewer to read them. They are similar to the ones shown at the end of movies based on true stories, but they are shown throughout, typically between scenes.

- Hosted narrator

In this style, there is a host who appears on camera, conducts interviews, and who also does voice-overs.

The Look of Silence (2014) Joshua Oppenheimer

Other forms

Docufiction

Docufiction is a hybridgenre from two basic ones, fiction film and documentary, practiced since the first documentary films were made.

Fake-fiction

Fake-fiction is a genre which deliberately presents real, unscripted events in the form of a fiction film, making them appear as staged. The concept was introduced[25] by Pierre Bismuth to describe his 2016 film Where is Rocky II?.

Where is Rocky 2 (2016) Pierre Bismuth

DVD documentary

A DVD documentary is a documentary film of indeterminate length that has been produced with the sole intent of releasing it for direct sale to the public on DVD(s), as different from a documentary being made and released first on television or on a cinema screen (a.k.a. theatrical release) and subsequently on DVD for public consumption.

This form of documentary release is becoming more popular and accepted as costs and difficulty with finding TV or theatrical release slots increases. It is also commonly used for more ‘specialist’ documentaries, which might not have general interest to a wider TV audience. Examples are military, cultural arts, transport, sports, etc..

Compilation films

Compilation films were pioneered in 1927 by Esfir Schub with The Fall of the Romanov Dynasty. More recent examples include Point of Order (1964), directed by Emile de Antonio about the McCarthy hearings, and The Atomic Cafe which is made entirely out of found footage that various agencies of the U.S. government made about the safety of nuclear radiation (for example, telling troops at one point that it is safe to be irradiated as long as they keep their eyes and mouths shut). Similarly, The Last Cigarette combines the testimony of various tobacco company executives before the U.S. Congress with archival propaganda extolling the virtues of smoking.

Point of Order (1964) Emile De Antonio

Poetic documentaries, which first appeared in the 1920s, were a sort of reaction against both the content and the rapidly crystallizing grammar of the early fiction film. The poetic mode moved away from continuity editing and instead organized images of the material world by means of associations and patterns, both in terms of time and space.

Well-rounded characters—”lifelike people”—were absent; instead, people appeared in these films as entities, just like any other, that are found in the material world. The films were fragmentary, impressionistic, lyrical. Their disruption of the coherence of time and space—a coherence favored by the fiction films of the day—can also be seen as an element of the modernist counter-model of cinematic narrative. The “real world”—Nichols calls it the “historical world”—was broken up into fragments and aesthetically reconstituted using film form. Examples of this style include Joris Ivens’ Rain (1928), which records a passing summer shower over Amsterdam; László Moholy-Nagy’s Play of Light: Black, White, Grey (1930), in which he films one of his own kinetic sculptures, emphasizing not the sculpture itself but the play of light around it; Oskar Fischinger’s abstract animated films; Francis Thompson’s N.Y., N.Y. (1957), a city symphony film; and Chris Marker’s Sans Soleil (1982).

Expository documentaries speak directly to the viewer, often in the form of an authoritative commentary employing voiceover or titles, proposing a strong argument and point of view. These films are rhetorical, and try to persuade the viewer. (They may use a rich and sonorous male voice.) The (voice-of-God) commentary often sounds ‘objective’ and omniscient. Images are often not paramount; they exist to advance the argument. The rhetoric insistently presses upon us to read the images in a certain fashion. Historical documentaries in this mode deliver an unproblematic and ‘objective’ account and interpretation of past events.

Examples: TV shows and films like Biography, America’s Most Wanted, many science and nature documentaries, Ken Burns’ The Civil War (1990), Robert Hughes’ The Shock of the New (1980), John Berger’s Ways Of Seeing (1974), Frank Capra’s wartime Why We Fight series, and Pare Lorentz’s The Plow That Broke The Plains (1936).

Prelude to War – Why We Fight (1942) Frank Capra

Observational

Observational documentaries attempt to simply and spontaneously observe lived life with a minimum of intervention. Filmmakers who worked in this subgenre often saw the poetic mode as too abstract and the expository mode as too didactic. The first observational docs date back to the 1960s; the technological developments which made them possible include mobile lighweight cameras and portable sound recording equipment for synchronized sound. Often, this mode of film eschewed voice-over commentary, post-synchronized dialogue and music, or re-enactments. The films aimed for immediacy, intimacy, and revelation of individual human character in ordinary life situations.

Types

Participatory documentaries believe that it is impossible for the act of filmmaking to not influence or alter the events being filmed. What these films do is emulate the approach of the anthropologist: participant-observation. Not only is the filmmaker part of the film, we also get a sense of how situations in the film are affected or altered by their presence. Nichols: “The filmmaker steps out from behind the cloak of voice-over commentary, steps away from poetic meditation, steps down from a fly-on-the-wall perch, and becomes a social actor (almost) like any other. (Almost like any other because the filmmaker retains the camera, and with it, a certain degree of potential power and control over events.)” The encounter between filmmaker and subject becomes a critical element of the film. Rouch and Morin named the approach cinéma vérité, translating Dziga Vertov’s kinopravda into French; the “truth” refers to the truth of the encounter rather than some absolute truth.

Reflexive documentaries do not see themselves as a transparent window on the world; instead, they draw attention to their own constructedness, and the fact that they are representations. How does the world get represented by documentary films? This question is central to this subgenre of films. They prompt us to “question the authenticity of documentary in general.” It is the most self-conscious of all the modes, and is highly skeptical of ‘realism’. It may use Brechtian alienation strategies to jar us, in order to ‘defamiliarize’ what we are seeing and how we are seeing it.

Performative documentaries stress subjective experience and emotional response to the world. They are strongly personal, unconventional, perhaps poetic and/or experimental, and might include hypothetical enactments of events designed to make us experience what it might be like for us to possess a certain specific perspective on the world that is not our own, e.g. that of black, gay men in Marlon Riggs’s Tongues Untied (1989) or Jenny Livingston’s Paris Is Burning (1991). This subgenre might also lend itself to certain groups (e.g. women, ethnic minorities, gays and lesbians, etc.) to ‘speak about themselves.’ Often, a battery of techniques, many borrowed from fiction or avant-garde films, are used. Performative docs often link up personal accounts or experiences with larger political or historical realities.

Chronique D’Un Ete (1960) Jean Rouch and Edgar Morin

Translation

There are several challenges associated with translation of documentaries. The main two are working conditions and problems with terminology.

Working conditions

Documentary translators very often have to meet tight deadlines. Normally, the translator has between five and seven days to hand over the translation of a 90-minute programme. Dubbing studios typically give translators a week to translate a documentary, but in order to earn a good salary, translators have to deliver their translations in a much shorter period, usually when the studio decides to deliver the final programme to the client sooner or when the broadcasting channel sets a tight deadline, e.g. on documentaries discussing the latest news.[26]

Another problem is the lack of postproduction script or the poor quality of the transcription. A correct transcription is essential for a translator to do their work properly, however many times the script is not even given to the translator, which is a major impediment since documentaries are characterised by “the abundance of terminological units and very specific proper names”.[27] When the script is given to the translator, it is usually poorly transcribed or outright incorrect making the translation unnecessary difficult and demanding because all of the proper names and specific terminology have to be correct in a documentary programme in order for it to be a reliable source of information, hence the translator has to check every term on their own. Such mistakes in proper names are for instance: “Jungle Reinhard instead of Django Reinhart, Jorn Asten instead of Jane Austen, and Magnus Axle instead of Aldous Huxley”.[27]

Fata Morgana (1971) Werner Herzog – Original Release German Poster (1971)

Terminology

The process of translation of a documentary programme requires working with very specific, often scientific terminology. Documentary translators usually are not specialist in a given field. Therefore, they are compelled to undertake extensive research whenever asked to make a translation of a specific documentary programme in order to understand it correctly and deliver the final product free of mistakes and inaccuracies. Generally, documentaries contain a large amount of specific terms, with which translators have to familiarise themselves on their own, for example:

The documentary Beetles, Record Breakers makes use of 15 different terms to refer to beetles in less than 30 minutes (longhorn beetle, cellar beetle, stag beetle, burying beetle or gravediggers, sexton beetle, tiger beetle, bloody nose beetle, tortoise beetle, diving beetle, devil’s coach horse, weevil, click beetle, malachite beetle, oil beetle, cockchafer), apart from mentioning other animals such as horseshoe bats or meadow brown butterflies.[28]

This poses a real challenge for the translators because they have to render the meaning, i.e. find an equivalent, of a very specific, scientific term in the target language and frequently the narrator uses a more general name instead of a specific term and the translator has to rely on the image presented in the programme to understand which term is being discussed in order to transpose it in the target language accordingly.[29] Additionally, translators of minorised languages often have to face another problem: some terms may not even exist in the target language. In such case, they have to create new terminology or consult specialists to find proper solutions. Also, sometimes the official nomenclature differs from the terminology used by actual specialists, which leaves the translator to decide between using the official vocabulary that can be found in the dictionary, or rather opting for spontaneous expressions used by real experts in real life situations.[30]

The Seven Five/ Precinct Seven Five (2014) Tiller Russell

See also

- Actuality film

- Animated documentary

- Citizen media

- Concert film

- Dance film

- Docudrama

- Documentary mode

- Ethnofiction

- Ethnographic film

- Filmmaking

- List of documentary films

- List of documentary film festivals

- List of directors and producers of documentaries

- Mockumentary

- Mondo film

- Nature documentary

- Outline of film

- Participatory video

- Political cinema

- Public-access television

- Reality film

- Rockumentary

- Sponsored film

- Travel documentary

- Visual anthropology

- Web documentary

- Women’s cinema

Some documentary film awards

- Grierson Awards

- Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature

- Joris Ivens Award, International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam (IDFA), (named after Joris Ivens)

- Filmmaker Award, Margaret Mead Film Festival

- Grand Prize, Visions du Réel

Grierson Awards

Notes and references

- Jump up^ oed.com

- Jump up^ Nichols, Bill. ‘Foreword’, in Barry Keith Grant and Jeannette Sloniowski (eds.) Documenting The Documentary: Close Readings of Documentary Film and Video. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1997

- Jump up^ Scott MacKenzie, Film Manifestos and Global Cinema Cultures: A Critical Anthology, Univ of California Press 2014, ISBN 9780520957411, p.520

- Jump up^ James Chapman, “Film and History. Theory and History” part “Film as historical source” p.73-75, Palgrave Macmillan, 2013, ISBN 9781137367327

- Jump up^ Ann Curthoys, Marilyn Lake Connected worlds: history in transnational perspective, Volume 2004 p.151. Australian National University Press

- Jump up^ Re-Thinking Grierson: The Ideology of John Grierson

- Jump up^ Pare Lorentz Film Library – FDR and Film

- Jump up^ Larry Ward (Fall 2008). “Introduction” (PDF). Lecture Notes for the BA in Radio–TV–Film (RTVF). 375: Documentary Film & Television. California State University, Fullerton (College of communications): 4, slide 12.

- Jump up^ Charles Ford, Robert Hammond: Polish Film: A Twentieth Century History. McFarland, 2005. ISBN 9781476608037, p.10.

- Jump up^ Journal of Film Preservation, nr. 70, November 2005.

- Jump up^ Mircea Dumitrescu, O privire critică asupra filmului românesc, Brașov, 2005, ISBN 978-973-9153-93-5

- Jump up^ Rîpeanu, Bujor T. Filmul documentar 1897–1948, Bucharest, 2008, ISBN 978-973-7839-40-4

- Jump up^ Ţuţui, Marian, A short history of the Romanian films at the Romanian National Cinematographic Center. Archived April 11, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- Jump up^ The Works of Gheorghe Marinescu, 1967 report.

- Jump up^ Excerpts of prof. dr. Marinescu’s science films. Archived February 26, 2015, at the Wayback Machine.

- Jump up^ Miriam Hansen, Babel and Babylon: Spectatorship in American Silent Film, 2005.

- Jump up^ Rees, A.L. (2011). A History of Experimental Film and Video (2nd Edition). Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-84457-436-0.

- Jump up^ Grierson, John. ‘First Principles of Documentary’, in Kevin Macdonald & Mark Cousins (eds.) Imagining Reality: The Faber Book of Documentary. London: Faber and Faber, 1996

- Jump up^ Les raquetteurs – NFB – Collection

- Jump up^ Struggles for Representation African American Documentary Film and Video, edited by Phyllis R. Klotman and Janet K. Cutler,

- Jump up^ Wood, Daniel B. (2 June 2006). “In ‘docu-ganda’ films, balance is not the objective”. Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 2006-06-06.

- Jump up^ Johnson, Ted (2015-06-19). “AFI Docs: Filmmakers Get Savvier About Fueling Social Change”. Variety. Retrieved 2016-06-23.

- Jump up^ “social impact campaigns”. http://www.azuremedia.org. Retrieved 2016-06-23.

- Jump up^ indiewire.com, “Festivals: Post-Sundance 2001; Docs Still Face Financing and Distribution Challenges.” February 8, 2001.

- Jump up^ Campion, Chris (2015-02-11). “Where is Rocky II? The 10-year desert hunt for Ed Ruscha’s missing boulder”. The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2016-10-22.

- Jump up^ Matamala, A. (2009). Main Challenges in the Translation of Documentaries. In J. Cintas (Ed.), New Trends in Audiovisual Translation (pp. 109-120). Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters, p. 110-111.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Matamala, A. (2009). Main Challenges in the Translation of Documentaries. In J. Cintas (Ed.), New Trends in Audiovisual Translation (pp. 109-120). Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters, p. 111

- Jump up^ Matamala, A. (2009). Main Challenges in the Translation of Documentaries. In J. Cintas (Ed.), New Trends in Audiovisual Translation (pp. 109-120). Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters, p. 113

- Jump up^ Matamala, A. (2009). Main Challenges in the Translation of Documentaries. In J. Cintas (Ed.), New Trends in Audiovisual Translation (pp. 109-120). Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters, p. 113-114

- Jump up^ Matamala, A. (2009). Main Challenges in the Translation of Documentaries. In J. Cintas (Ed.), New Trends in Audiovisual Translation (pp. 109-120). Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters, p. 114-115

Grizzly Man (2005) Werner Herzog

Sources and bibliography

- Aitken, Ian (ed.). Encyclopedia of the Documentary Film. New York: Routledge, 2005. ISBN 978-1-57958-445-0.

- Barnouw, Erik. Documentary: A History of the Non-Fiction Film, 2nd rev. ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 1993. ISBN 978-0-19-507898-5. Still a useful introduction.

- Ron Burnett. “Reflections on the Documentary Cinema”

- Burton, Julianne (ed.). The Social Documentary in Latin America. Pittsburgh, Penn.: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1990. ISBN 978-0-8229-3621-3.

- Dawson, Jonathan. “Dziga Vertov”.

- Ellis, Jack C., and Betsy A. McLane. “A New History of Documentary Film.” New York: Continuum International, 2005. ISBN 978-0-8264-1750-3, ISBN 978-0-8264-1751-0.

- Goldsmith, David A.The Documentary Makers: Interviews with 15 of the Best in the Business. Hove, East Sussex: RotoVision, 2003. ISBN 978-2-88046-730-2.

- Klotman, Phyllis R. and Culter, Janet K.(eds.). Struggles for Representation: African American Documentary Film and Video Bloomington and Indianapolis, IN: Indiana University Press, 1999. ISBN 978-0-253-21347-1.

- Leach, Jim, and Jeannette Sloniowski (eds.). Candid Eyes: Essays on Canadian Documentaries. Toronto; Buffalo: University of Toronto Press, 2003. ISBN 978-0-8020-4732-8, ISBN 978-0-8020-8299-2.

- Nichols, Bill. Introduction to Documentary, Bloomington, Ind.: Indiana University Press, 2001. ISBN 978-0-253-33954-6, ISBN 978-0-253-21469-0.

- Nichols, Bill. Representing Reality: Issues and Concepts in Documentary. Bloomington, Ind.: Indiana University Press, 1991. ISBN 978-0-253-34060-3, ISBN 978-0-253-20681-7.

- Nornes, Markus. Forest of Pressure: Ogawa Shinsuke and Postwar Japanese Documentary. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007. ISBN 978-0-8166-4907-5, ISBN 978-0-8166-4908-2.

- Nornes, Markus. Japanese Documentary Film: The Meiji Era through Hiroshima. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2003. ISBN 978-0-8166-4045-4, ISBN 978-0-8166-4046-1.

- Rotha, Paul, Documentary diary; An Informal History of the British Documentary Film, 1928–1939. New York: Hill and Wang, 1973. ISBN 978-0-8090-3933-3.

- Saunders, Dave. Direct Cinema: Observational Documentary and the Politics of the Sixties. London: Wallflower Press, 2007. ISBN 978-1-905674-16-9, ISBN 978-1-905674-15-2.

- Saunders, Dave. Documentary: The Routledge Film Guidebook. London: Routledge, 2010.

- Tobias, Michael. The Search for Reality: The Art of Documentary Filmmaking. Studio City, CA: Michael Wiese Productions 1997. ISBN 0-941188-62-0

- Walker, Janet, and Diane Waldeman (eds.). Feminism and Documentary. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999. ISBN 978-0-8166-3006-6, ISBN 978-0-8166-3007-3.

- Wyver, John. The Moving Image: An International History of Film, Television & Radio. Oxford: Basil Blackwell Ltd. in association with the British Film Institute, 1989. ISBN 978-0-631-15529-4.

- Murdoch.edu, Documentary—reading list

Ethnographic film

- Emilie de Brigard, “The History of Ethnographic Film,” in Principles of Visual Anthropology, ed. Paul Hockings. Berlin and New York: Mouton de Gruyter, 1995, pp. 13–43.

- Leslie Devereaux, “Cultures, Disciplines, Cinemas,” in Fields of Vision. Essays in Film Studies, Visual Anthropology and Photography, ed. Leslie Devereaux & Roger Hillman. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995, pp. 329–339.

- Faye Ginsburg, Lila Abu-Lughod and Brian Larkin (eds.), Media Worlds: Anthropology on New Terrain. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2002. ISBN 978-0-520-23231-0.

- Anna Grimshaw, The Ethnographer’s Eye: Ways of Seeing in Modern Anthropology. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2001. ISBN 978-0-521-77310-2.

- Karl G. Heider, Ethnographic Film. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1994.

- Luc de Heusch, Cinéma et Sciences Sociales, Paris: UNESCO, 1962. Published in English as The Cinema and Social Science. A Survey of Ethnographic and Sociological Films. UNESCO, 1962.

- Fredric Jameson, Signatures of the Visible. New York & London: Routledge, 1990.

- Pierre-L. Jordan, Premier Contact-Premier Regard, Marseille: Musées de Marseille. Images en Manoeuvres Editions, 1992.

- André Leroi-Gourhan, “Cinéma et Sciences Humaines. Le Film Ethnologique Existe-t-il?,” Revue de Géographie Humaine et d’Ethnologie 3 (1948), pp. 42–50.

- David MacDougall, Transcultural Cinema. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1998. ISBN 978-0-691-01234-6.

- David MacDougall, “Whose Story Is It?,” in Ethnographic Film Aesthetics and Narrative Traditions, ed. Peter I. Crawford and Jan K. Simonsen. Aarhus, Intervention Press, 1992, pp. 25–42.

- Fatimah Tobing Rony, The Third Eye: Race, Cinema and Ethnographic Spectacle. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1996. ISBN 978-0-8223-1840-8.

- Georges Sadoul, Histoire Générale du Cinéma. Vol. 1, L’Invention du Cinéma 1832–1897. Paris: Denöel, 1977, pp. 73–110.

- Pierre Sorlin, Sociologie du Cinéma, Paris: Aubier Montaigne, 1977, pp. 7–74.

- Charles Warren, “Introduction, with a Brief History of Nonfiction Film,” in Beyond Document. Essays on Nonfiction Film, ed. Charles Warren. Hanover and London: Wesleyan University Press, 1996, pp. 1–22.

- Ismail Xavier, “Cinema: Revelação e Engano,” in O Olhar, ed. Adauto Novaes. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 1993, pp. 367–384.

Kevin Brownlow and David Shephard at Academy’s 2010 Governor’s Dinner

Kevin Brownlow and David Shephard at Academy’s 2010 Governor’s Dinner

You must be logged in to post a comment.