Prepared by Daniel B Miller

Barbara Stanwyck (born Ruby Catherine Stevens; July 16, 1907 – January 20, 1990) was an American actress, model and dancer.

She was a film and television star, known during her 60-year career as a consummate and versatile professional with a strong, realistic screen presence, and a favorite of directors including Cecil B. DeMille, Fritz Lang, and Frank Capra.

After a short but notable career as a stage actress in the late 1920s, she made 85 films in 38 years in Hollywood, before turning to television.

Orphaned at the age of four and partially raised in foster homes, by 1944 Stanwyck had become the highest-paid woman in the United States.

She was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Actress four times, for Stella Dallas (1937), Ball of Fire (1941), Double Indemnity (1944) and Sorry, Wrong Number (1948). For her television work, she won three Emmy Awards, for The Barbara Stanwyck Show (1961), The Big Valley (1966) and The Thorn Birds (1983).

Her performance in The Thorn Birds also won her a Golden Globe. She received an Honorary Oscar at the 1982 Academy Award ceremony and the Golden Globe Cecil B. DeMille Award in 1986. She was also the recipient of honorary lifetime awards from the American Film Institute (1987), the Film Society of Lincoln Center (1986), the Los Angeles Film Critics Association (1981) and the Screen Actors Guild (1967).

Stanwyck received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame in 1960, and was ranked as the 11th greatest female star of classic American cinema by the American Film Institute.[1]

As Sugarpuss O’Shea in Ball of Fire (Howard Hawks, 1941) Promo

In her most celebrated role as Phyllis Dietrichson in Double Indemnity ( Billy Wilder, 1942)

Contents

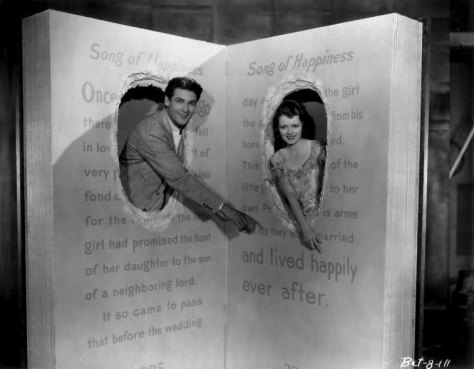

As Barbara O’Neill in Ten Cents A Dance ( Lionel Barrymore and Edward Buzzell, 1931)

Early life

Barbara Stanwyck was born Ruby Catherine Stevens on July 16, 1907, in Brooklyn, New York.[2]

She was the fifth child of Byron E. and Catherine Ann Stevens. Her parents were working-class. Her father was a native of Massachusetts and her mother was an immigrant from Nova Scotia.[3][4]

Ruby Catherine Stevens aged 3 in 1910

Ruby was of English and Scottish ancestry, by her father and mother, respectively.[2] When Ruby was four, her mother died of complications from a miscarriage after a drunken stranger accidentally knocked her off a moving streetcar.[5]

Ruby and Mildred in 1910

Two weeks after the funeral, Byron Stevens joined a work crew digging the Panama Canal and was never seen again.[6] Ruby and her brother Byron were raised by their elder sister Mildred, who was nineteen years older than Ruby.[6][7] When Mildred got a job as a showgirl, Ruby and Byron were placed in a series of foster homes (as many as four in a year), from which young Ruby often ran away.[8][Note 1]

Ruby aged 5 in 1912

| “I knew that after fourteen I’d have to earn my own living, but I was willing to do that … I’ve always been a little sorry for pampered people, and of course, they’re ‘very’ sorry for me.” |

| Barbara Stanwyck, 1937[10] |

Ruby toured with Mildred during the summers of 1916 and 1917, and practiced her sister’s routines backstage.[9]Watching the movies of Pearl White, whom Ruby idolized, also influenced her drive to be a performer.[11]

Ruby Stevens in her mid teens

At the age of 14, she dropped out of school to take a job wrapping packages at a department store in Brooklyn.[12] Ruby never attended high school, “although early biographical thumbnail sketches had her attending Brooklyn’s famous Erasmus Hall High School.”[13]

Soon afterward, she took a job filing cards at the Brooklyn telephone office for $14 a week, which allowed her to become financially independent.[14] She disliked both jobs; her real goal was to enter show business, even as her sister Mildred discouraged the idea.

Ruby Stevens in her late teens

She then took a job cutting dress patterns for Vogue magazine, but because customers complained about her work, she was fired.[10] Her next job was as a typist for the Jerome H. Remick Music Company, a job she reportedly enjoyed. However, her continuing ambition was to work in show business, and her sister finally gave up trying to dissuade her.[15]

Ruby Stevens in 1922

Ziegfeld girl and Broadway success

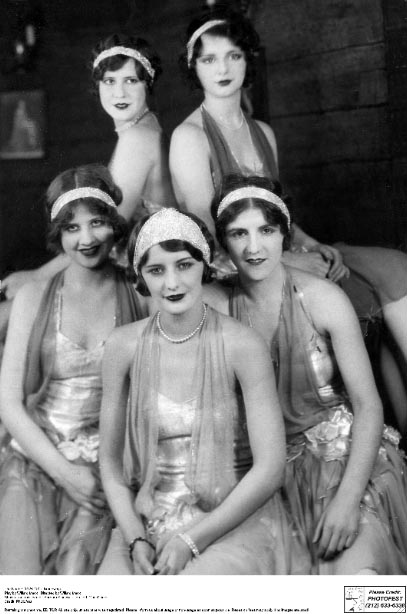

Ruby Stevens performing with Ziegfeld Girls 1920s

In 1923, a few months before her 16th birthday, Ruby auditioned for a place in the chorus at the Strand Roof, a night club over the Strand Theatre in Times Square.[16]

A few months later, she obtained a job as a dancer in the 1922 and 1923 seasons of the Ziegfeld Follies, dancing at the New Amsterdam Theater. “I just wanted to survive and eat and have a nice coat,” Stanwyck said.[17][18]

Ruby Stevens as a Ziegfeld Girl (c. 1924)

Ruby Stevens from Ziegfeld Girl to Broadway (c. 1927)

For the next several years, she worked as a chorus girl, performing from midnight to seven a.m. at nightclubs owned by Texas Guinan. She also occasionally served as a dance instructor at a speakeasy for gays and lesbians owned by Guinan.[19]

Mary Louise Cecilia Guinan AKA Texas Guinan

One of her good friends during those years was pianist Oscar Levant, who described her as being “wary of sophisticates and phonies.”[17]

Billy LaHiff, who owned a popular pub frequented by showpeople, introduced Ruby in 1926 to impresario Willard Mack.[20]

Barbara Stanwyck’s best friend during the Ziegfield years, pianist Oscar Levant

Mack was casting his play The Noose, and LaHiff suggested that the part of the chorus girl be played by a real one. Mack agreed, and after a successful audition gave the part to Ruby.[21] She co-starred with Rex Cherryman and Wilfred Lucas.[22] As initially staged, the play was not a success.[23]

In an effort to improve it, Mack decided to expand Ruby’s part to include more pathos.[24] The Noose re-opened on October 20, 1926, and became one of the most successful plays of the season, running on Broadway for nine months and 197 performances.[18] At the suggestion of either Mack or David Belasco, Ruby changed her name to Barbara Stanwyck by combining the first name of her character, Barbara Frietchie, with the last name of another actress in the play, Jane Stanwyck.[23]

Ruby Stevens with her new stage name as Barbara Stanwyck with Mae Clarke, Dorothy Shepherd and Erenay in The Noose on Broadway 1926

Barbara Stanwyck in The Noose on Broadway, 1926

Stanwyck became a Broadway star soon afterward, when she was cast in her first leading role in Burlesque (1927). She received rave reviews, and it was a huge hit.[25] Film actor Pat O’Brien would later say on a talk show in the 1960s, “The greatest Broadway show I ever saw was a play in the 1920s called ‘Burlesque’.” In Arthur Hopkins‘ autobiography, To a Lonely Boy, he described how he came to cast Stanwyck:

After some search for the girl, I interviewed a nightclub dancer who had just scored in a small emotional part in a play that did not run (The Noose). She seemed to have the quality I wanted, a sort of rough poignancy. She at once displayed more sensitive, easily expressed emotion than I had encountered since Pauline Lord. She and (Hal) Skelly were the perfect team, and they made the play a great success. I had great plans for her, but the Hollywood offers kept coming. There was no competing with them. She became a picture star. She is Barbara Stanwyck.

He also called Stanwyck “The greatest natural actress of our time,” noting with sadness, “One of the theater’s great potential actresses was embalmed in celluloid.”[26]

Barbara Stanwyck in Burlesque on Broadway, 1927

Around this time, Stanwyck was given a screen test by producer Bob Kane for his upcoming 1927 silent film Broadway Nights. She lost the lead role because she could not cry in the screen test, but was given a minor part as a fan dancer. This was Stanwyck’s first film appearance.[27]

While playing in Burlesque, Stanwyck was introduced to her future husband, actor Frank Fay, by Oscar Levant.[28] Stanwyck and Fay were married on August 26, 1928, and soon moved to Hollywood.[8]

Barbara Stanwyck’s first screen appearance was as a fan dancer in Broadway Nights (Joseph C Boyle, 1927)

Broadway Nights (Joseph C Boyle, 1927)

Barbara Stanwyck and Frank Fay (c 1928), The Billy Rose Theatre Collection, The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts

Barbara Stanwyck and Frank Fay (c 1929)

Film career

Barbara Stanwyck with Rod La Rocque in The Locked Door (1927)

Stanwyck’s first sound film was The Locked Door (1929), followed by Mexicali Rose, released in the same year.

Neither film was successful; nonetheless, Frank Capra chose Stanwyck for his Ladies of Leisure (1930).[18]

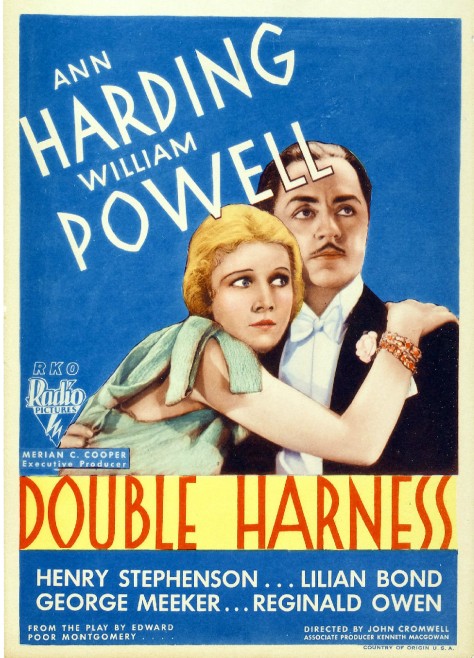

Numerous prominent roles followed, among them the children’s nurse who saves two little girls from being gradually starved to death by Clark Gable‘s vicious character in Night Nurse (1931); So Big!, as a valiant Midwest farm woman (1932); Shopworn 1932; the ambitious woman from “the wrong side of the tracks” in Baby Face (1933); the self-sacrificing title character in Stella Dallas (1937); Molly Monahan in Union Pacific (1939) with Joel McCrea; Meet John Doe, as an ambitious newspaperwoman with Gary Cooper (1941); the con artist who falls for her intended victim (played by Henry Fonda) in The Lady Eve (1941); the extremely successful, independent doctor Helen Hunt in You Belong to Me (1941), also with Fonda; a nightclub performer who gives a professor (played by Gary Cooper) a better understanding of “modern English” in the comedy Ball of Fire (1941); the woman who talks an infatuated insurance salesman (Fred MacMurray) into killing her husband in Double Indemnity (1944); the columnist caught up in white lies and a holiday romance in Christmas in Connecticut (1945); and the doomed wife in Sorry, Wrong Number (1948). She also played a doomed concert pianist in The Other Love (1947); the piano music was played by Ania Dorfmann, who drilled Stanwyck for three hours a day until she was able to move her arms and hands to match the music.[29]

Stanwyck was reportedly one of the many actresses considered for the role of Scarlett O’Hara in Gone with the Wind(1939), although she did not receive a screen test. In 1944 she was the highest-paid woman in the United States.[18]

Barbara Stanwyck in her first screen role as Ann Carter in The Locked Door (George Fitzmaurice, 1929)

Barbara Stanwyck as Mexicali Rose in Mexicali Rose AKA The Girl From Mexico (Erle C Kenton, 1929)

Barbara Stanwyck as Kay Arnold in Ladies of Leisure (Frank Capra, 1930) her major Hollywood breakthrough

Barbara Stanwyck as Kay Arnold in Ladies of Leisure (Frank Capra, 1930) her major Hollywood breakthrough

Barbara Stanwyck as Lora Hart in her second big Hollywood hit Night Nurse (William Wellman, 1931)

Barbara Stanwyck as Lora Hart in her second big Hollywood hit Night Nurse (William Wellman, 1931)

Barbara Stanwyck as Florence Fallon in The Miracle Woman (Frank Capra, 1931)

Barbara Stanwyck as Lulu in Forbidden (Frank Capra, 1932)

Barbara Stanwyck as Megan in The Bitter Tea Of General Yen (Frank Capra, 1932)

Barbara Stanwyck in one of her most controversial roles as Lily in Baby Face (Alfred E Green, 1933)

Barbara Stanwyck in one of her most controversial roles as Lily in Baby Face (Alfred E Green, 1933)

Barbara Stanwyck as Nan Taylor in Ladies They Talk About (Howard Bretherton and William Keighley, 1933)

Barbara Stanwyck as Shelby Barret Wyatt in The Woman in Red (Robert Florey, 1935)

Barbara Stanwyck as Kitty Lane in Shopworn (Nick Grinde, 1932)

Barbara Stanwyck as Drue Van Allen in Red Salute/Runaway Daughter/ Arms and the Girl (Sidney Lanfield, 1935)

Barbara Stanwyck as Annie Oakley in Annie Oakley (George Stevens, 1935)

Barbara Stanwyck as Stella Dallas in Stella Dallas (King Vidor, 1937)

Barbara Stanwyck as Mollie Monahan in Union Pacific (Cecil B DeMille,1939)

Barbara Stanwyck as Mollie Monahan in Union Pacific (Cecil B DeMille,1939)

Barbara Stanwyck as Ann Mitchell in Meet John Doe (Frank Capra,1941)

Barbara Stanwyck as Ann Mitchell in Meet John Doe (Frank Capra,1941)

Barbara Stanwyck as Jean in The Lady Eve (Preston Sturges, 1941)

Barbara Stanwyck as Sugarpuss O’Shea in Ball of Fire (Howard Hawks,1941)

Barbara Stanwyck as Sugarpuss O’Shea in Ball of Fire (Howard Hawks,1941) Promo

Barbara Stanwyck as Sugarpuss O’Shea in Ball of Fire (Howard Hawks,1941)

Barbara Stanwyck as Deborah Hoople aka Dixie Daisy in Lady of Burlesque (William Wellman, 1943)

Barbara Stanwyck as Deborah Hoople aka Dixie Daisy in Lady of Burlesque (William Wellman, 1943)

Barbara Stanwyck in her most celebrated role as Phyllis Dietrichson in Double Indemnity (Billy Wilder, 1944)

Barbara Stanwyck in her most celebrated role as Phyllis Dietrichson in Double Indemnity (Billy Wilder, 1944)

Barbara Stanwyck in her most celebrated role as Phyllis Dietrichson in Double Indemnity (Billy Wilder, 1944)

Barbara Stanwyck in her most celebrated role as Phyllis Dietrichson in Double Indemnity (Billy Wilder, 1944)

Barbara Stanwyck as Martha Ivers in The Strange Love of Martha Ivers (Lewis Milestone,1946)

Barbara Stanwyck as Martha Ivers in The Strange Love of Martha Ivers (Lewis Milestone,1946)

Barbara Stanwyck as Karen Duncan in The Other Love (Andre DeToth, 1947)

Barbara Stanwyck as Karen Duncan in The Other Love (Andre DeToth, 1947)

Barbara Stanwyck as Leona Stevenson in Sorry Wrong Number (Anatole Litvak, 1948)

Barbara Stanwyck as Jessie Bourne in East Side, West Side (Mervyn LeRoy, 1949)

Barbara Stanwyck as Jessie Bourne in East Side, West Side (Mervyn LeRoy, 1949)

Barbara Stanwyck as Vance Jeffords in The Furies (Anthony Mann, 1950)

Barbara Stanwyck as Thelma Jordon in The File on Thelma Jordon (Robert Siodmak, 1950)

Barbara Stanwyck as Thelma Jordon in The File on Thelma Jordon (Robert Siodmak, 1950)

Barbara Stanwyck as Helen Ferguson/Patrice Harkness in No Man of Her Own (Mitchell Leisen, 1950)

Barbara Stanwyck as Mae Doyle D’Amato in Clash by Night (Fritz Lang, 1952)

Barbara Stanwyck as Mae Doyle D’Amato in Clash by Night (Fritz Lang, 1952)

Barbara Stanwyck as Julia Sturges in Titanic (Jean Negulesco, 1953)

Barbara Stanwyck as Helen Stilwin in Jeopardy (John Sturges, 1953)

Barbara Stanwyck as Naomi Murdoch in All I Desire (Douglas Sirk, 1953)

Barbara Stanwyck as Norma Miller Vale in There’s Always Tomorrow (Douglas Sirk, 1955)

Barbara Stanwyck as Gwen Moore in Escape From Burma (Allan Dwan, 1955)

Barbara Stanwyck as Jessica Drummond in 40 Guns (Samuel Fuller, 1957)

| “That is the kind of woman that makes whole civilizations topple.” |

| Kathleen Howard of Stanwyck’s character in Ball of Fire[30] |

Pauline Kael, describing Stanwyck’s acting, wrote: “[She] seems to have an intuitive understanding of the fluid physical movements that work best on camera” and in reference to her early 1930s film work, “[E]arly talkies sentimentality … only emphasizes Stanwyck’s remarkable modernism.”[31]

Barbara Stanwyck with Fred MacMurray as Phyllis Dietrichson in Double Indemnity (Billy Wilder, 1944)

Many of her roles involved strong characters. In Double Indemnity, Stanwyck brought out the cruel nature of the “grim, unflinching murderess,” marking her as the “most notorious femme” in the film noir genre.[32] Yet, Stanwyck was known for her accessibility and kindness to the backstage crew on any film set.

She knew the names of their wives and children. Frank Capra said of Stanwyck: “She was destined to be beloved by all directors, actors, crews and extras. In a Hollywood popularity contest she would win first prize hands down.”[33]

Barbara Stanwyck with Frank Capra on the set of Forbidden (Frank Capra, 1932)

A consummate professional, when aged 50 she performed a stunt in Forty Guns. Her character had to fall off her horse and, her foot caught in the stirrup, be dragged by the galloping animal. This was so dangerous the movie’s professional stunt person refused to do it.[34] Her professionalism on film sets led her to be named an Honorary Member of the Hollywood Stuntmen’s Hall of Fame.[35]

Stanwyck played alongside Elvis Presley as a carnival owner in the movie Roustabout in 1964.

Barbara Stanwyck with Elvis Presley on the set of Rustabout (John Rich, 1964)

William Holden and Stanwyck were friends of long standing. When Stanwyck and Holden were presenting the Best Sound Oscar for 1977, Holden paused to pay a special tribute to her for saving his career when Holden was cast in the lead for Golden Boy (1939).

After a series of unsteady daily performances, he was about to be fired, but Stanwyck staunchly defended him, successfully standing up to the film producers. Shortly after Holden’s death, Stanwyck recalled the moment when receiving her honorary Oscar: “A few years ago I stood on this stage with William Holden as a presenter. I loved him very much, and I miss him. He always wished that I would get an Oscar. And so tonight, my golden boy, you got your wish.”[36]

Barbara Stanwyck and William Holden in Golden Boy (Rouben Mamoulian, 1939)

Television career

When Stanwyck’s film career declined in 1957, she moved to television. Her 1961 series The Barbara Stanwyck Show was not a ratings success but earned her an Emmy Award.[18] The Western series The Big Valley, which ran from 1965 to 1969 on ABC, made her one of the most popular actresses on television, winning her another Emmy.[18] She was billed as “Miss Barbara Stanwyck”. The story of her 1940 movie Remember the Night was used in an episode titled “Judgement in Heaven” (Season 1, Episode 15).

Barbara Stanwyck in Barbara Stanwyck Show – Judgement in Heaven (1965)

She also appeared in the television series The Untouchables with Robert Stack (1962–63), and in four episodes of Wagon Train as three different characters (1961–64).

Barbara Stanwyck and Robert Stack on the set of The Untouchables (1962-63)

Barbara Stanwyck in Wagon Train (1961-64)

Years later, Stanwyck earned her third Emmy for The Thorn Birds.[18] In 1985 she made three guest appearances in the primetime soap opera Dynasty prior to the launch of its short-lived spin-off series, The Colbys, in which she starred alongside Charlton Heston, Stephanie Beacham and Katharine Ross.

Unhappy with the experience, Stanwyck remained with the series for only one season (it lasted for two), and her role as Constance Colby Patterson would prove to be her last.[18] Earl Hamner Jr. (producer of The Waltons) had initially wanted Stanwyck for the lead role of Angela Channing in the 1980s soap opera Falcon Crest, but she turned it down and the role went to her best friend, Jane Wyman.

Barbara Stanwyck and Richard Chamberlain in Thorn Birds (1983)

Barbara Stanwyck in Dynasty / The Colbys – 3 Episodes (1981)

Personal life

Marriages and relationships

While playing in The Noose, Stanwyck reportedly fell in love with her married co-star, Rex Cherryman.[8]

Cherryman had become ill early in 1928 and his doctor advised him to take a sea voyage to Paris where he and Stanwyck had arranged to meet. While still at sea, he died of septic poisoning at the age of 31.[37]

Barbara Stanwyck and Rex Cherryman on the set of The Noose (1927)

On August 26, 1928, Stanwyck married her Burlesque co-star, Frank Fay. She and Fay later claimed they disliked each other at first, but became close after Cherryman’s death.[8] A botched abortion at the age of 15 had resulted in complications which left Stanwyck unable to have children, according to her biographer.[38]

After moving to Hollywood, the couple adopted a ten-month-old son on December 5, 1932. They named him Dion, later amending the name to Anthony Dion, nicknamed “Tony”. The marriage was a troubled one. Fay’s successful career on Broadway did not translate to the big screen, whereas Stanwyck achieved Hollywood stardom.

Fay was reportedly physically abusive to his young wife, especially when he was inebriated.[39][40] Some claim that this union was the basis for A Star Is Born.[41] The couple divorced on December 30, 1935. Stanwyck won custody of their adoptive son, whom she had raised with a strict authoritarian hand and demanding expectations.[42] Stanwyck and her son were estranged after his childhood, meeting only a few times after he became an adult. The child whom she had adopted in infancy “resembled her in just one respect: both were, effectively, orphans.”[43]

Barbara Stanwyck and Frank Fay (1932)

In 1936, while making the film His Brother’s Wife (1936), Stanwyck became involved with her co-star, Robert Taylor. Rather than a torrid romance, their relationship was more one of mentor and pupil. Stanwyck served as support and adviser to the younger Taylor, who had come from a small Nebraska town; she guided his career, and acclimated him to the sophisticated Hollywood culture.

Barbara Stanwyck and Robert Taylor on their wedding day (1939)

The couple began living together, sparking newspaper reports about the two. Stanwyck was hesitant to remarry after the failure of her first marriage. However, their 1939 marriage was arranged with the help of Taylor’s studio Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, a common practice in Hollywood’s golden age. Louis B. Mayer had insisted on the two stars marrying and went as far as presiding over arrangements at the wedding.[44][45]

She and Taylor enjoyed time together outdoors during the early years of their marriage, and owned acres of prime West Los Angeles property. Their large ranch and home in the Mandeville Canyon section of Brentwood, Los Angeles, is still referred to by the locals as the old “Robert Taylor ranch.”[46]

Barbara Stanwyck and Robert Taylor

Stanwyck and Taylor mutually decided in 1950 to divorce, and after his insistence, she proceeded with the official filing of the papers.[47] There have been many rumors regarding the cause of their divorce, but after World War II, Taylor had attempted to create a life away from Hollywood, and Stanwyck did not share that goal.[48]

Taylor had romantic affairs, and there were unsubstantiated rumors about Stanwyck having had affairs as well. After the divorce, they acted together in Stanwyck’s last feature film, The Night Walker (1964). She never remarried and cited Taylor as the love of her life, according to her friend and Big Valley co-star Linda Evans. She took his death in 1969 very hard, and took a long break from film and television work.[49]

Barbara Stanwyck and Robert Taylor

Barbara Stanwyck at Robert Taylor’s Funeral (1969)

Stanwyck was one of the best-liked actresses in Hollywood and was friends with many of her fellow actors (as well as crew members of her films and TV shows), including Joel McCrea and his wife Frances Dee, George Brent, Robert Preston, Henry Fonda (who had a lifelong crush on her[citation needed]), James Stewart, Linda Evans, Joan Crawford, Jack Benny and his wife Mary Livingstone, William Holden, Gary Cooper, Fred MacMurray, and many others.[50]

Barbara Stanwyck and Joel McCrea in Banjo On My Knee (1936)

Barbara Stanwyck and Henry Fonda in The Lady Eve (1941)

Barbara Stanwyck and Robert Preston in Union Pacific (1939)

Barbara Stanwyck and George Brent in My Reputation (1946)

Barbara Stanwyck with James Stewart

Barbara Stanwyck with Gary Cooper in Ball of Fire (1941)

Barbara Stanwyck with Fred McMurray in Remember the Night (1940)

Stanwyck had a romantic affair with actor Robert Wagner, whom she met on the set of Titanic (1953). Wagner, who was 22, and Stanwyck, who was 45 at the beginning of the relationship, had a four-year romance, which is described in Wagner’s memoir Pieces of My Heart (2008).[51] Stanwyck ended the relationship.[52] In the 1950s, Stanwyck reportedly also had a one-night stand with the much younger Farley Granger, which he wrote about in his autobiography Include Me Out: My Life from Goldwyn to Broadway (2007).[53][54][55]

Barbara Stanwyck with Robert Wagner in Titanic (1953)

Political views

Stanwyck opposed the presidency of Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

She felt that if someone from her disadvantaged background had risen to success, others should be able to prosper without government intervention or assistance.[56] For Stanwyck, indisputably, “hard work with the prospect of rich reward was the American way.” Stanwyck became an early member of the Motion Picture Alliance for the Preservation of American Ideals (MPA) after its founding in 1944.

SCREEN ACTOR ADOLPHE MENJOU (RIGHT) IS SWORN IN TO TESTIFY BEFORE HUAC. MENJOU WAS A ACTIVE MEMBER OF THE ‘MOTION PICTURE ALLIANCE FOR THE PRESERVATION OF AMERICAN IDEALS’, AN ANTI-COMMUNIST GROUP WHOSE MEMBERS INCLUDED JOHN WAYNE AND BARBARA STANWYCK. AT THE HUAC TABLE, (L-R): J. PARNEL THOMAS, RICHARD NIXON, A MOVIE CAMERAMAN, AND RICHARD VAIL. OCT. 21, 1947.

The mission of this group was to “… combat … subversive methods [used in the industry] to undermine and change the American way of life.” [57][58] It opposed both communist and fascist influences in Hollywood. She publicly supported the investigations of the House Un-American Activities Committee, her husband Robert Taylor appearing to testify as a friendly witness.[59]

Stanwyck shared conservative Republican affiliation with such contemporaries as Walt Disney, Hedda Hopper, Randolph Scott, Robert Young, Ward Bond, William Holden, Ginger Rogers, Jimmy Stewart, George Murphy, Gary Cooper, Bing Crosby, John Wayne, Walter Brennan, Shirley Temple, Bob Hope, Adolphe Menjou, Helen Hayes, director Frank Capra and her Double Indemnity co-star, Fred MacMurray.[60][61][62]

HUC Hearing in 1944

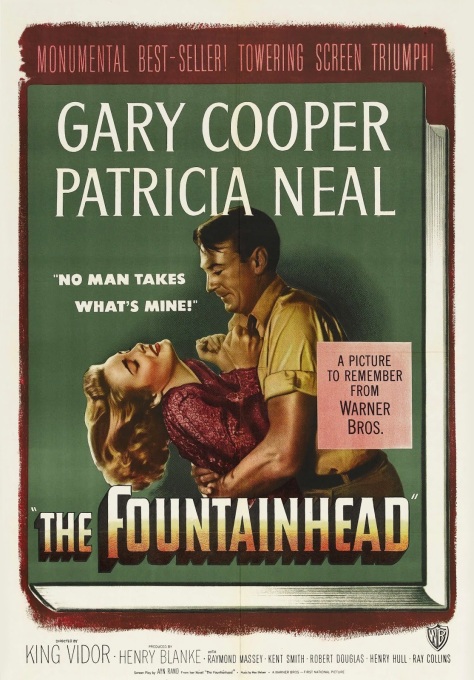

She was a fan of Objectivist author Ayn Rand, having persuaded Jack L. Warner at Warner Bros. to buy the rights to The Fountainhead before it was a best-seller, and writing to the author of her admiration of Atlas Shrugged.[56][63]

Religion

Stanwyck was originally a Protestant and was baptized in June 1916 by the Reverend J. Frederic Berg of the Protestant Dutch Reformed Church.[64]

She converted to Roman Catholicism when she married her first husband, Frank Fay.[65]

Brother

Her elder brother, Malcolm Byron Stevens (1905-1964), also became a prolific actor, though a much less successful one. According to IMDb, as Bert L. Stevens, he played hundreds of parts in film and television, but was only credited in two television episodes.[66] He appeared in two films that starred his famous sibling: The File on Thelma Jordon and No Man of Her Own, both released in 1950. He and actress Caryl Lincoln married in 1934 and remained together until his death from a heart attack. They had one son, Brian.

Malcolm Byron Stevens / Bert L Stevens

Later years and death

Stanwyck’s retirement years were active, with charity work outside the limelight. She was awakened in the middle of the night inside her home in the exclusive Trousdale section of Beverly Hills in 1981 by an intruder, who hit her on the head with his flashlight, then forced her into a closet while he robbed her of $40,000 in jewels.[67]

The following year, in 1982, while filming The Thorn Birds, the inhalation of special-effects smoke on the set may have caused her to contract bronchitis, which was compounded by her cigarette habit; she was a smoker from the age of nine until four years before her death.[68]

Barbara Stanwyck with Richard Chamberlain in The Thorn Birds (1983)

Stanwyck died on January 20, 1990, aged 82, of congestive heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) at Saint John’s Health Center in Santa Monica, California. She had indicated that she wanted no funeral service.[69] In accordance with her wishes, her remains were cremated and the ashes scattered from a helicopter over Lone Pine, California, where she had made some of her western films.[70][71]

Barbara Stanwyck Death Certificate

Barbara Stanwyck in Shopworn – promotional shot (Nick Grinde, 1932)

Filmography

- Broadway Nights (1927)

- The Locked Door (1929)

- Mexicali Rose (1929)

- Ladies of Leisure (1930)

- Illicit (1931)

- Ten Cents a Dance (1931)

- Night Nurse (1931)

- The Miracle Woman (1931)

- Forbidden (1932)

- Shopworn (1932)

- So Big (1932)

- The Purchase Price (1932)

- The Bitter Tea of General Yen (1933)

- Ladies They Talk About (1933)

- Baby Face (1933)

- Ever in My Heart (1933)

- Gambling Lady (1934)

- A Lost Lady (1934)

- The Secret Bride (1934)

- The Woman in Red (1935)

- Red Salute (1935)

- Annie Oakley (1935)

- A Message to Garcia (1936)

- The Bride Walks Out (1936)

- His Brother’s Wife (1936)

- Banjo on My Knee (1936)

- The Plough and the Stars (1936)

- Internes Can’t Take Money (1937)

- This Is My Affair (1937)

- Stella Dallas (1937)

- Breakfast for Two (1937)

- Always Goodbye (1938)

- The Mad Miss Manton (1938)

- Union Pacific (1939)

- Golden Boy (1939)

- Remember the Night (1940)

- The Lady Eve (1941)

- Meet John Doe (1941)

- You Belong to Me (1941)

- Ball of Fire (1941)

- The Great Man’s Lady (1942)

- The Gay Sisters (1942)

- Lady of Burlesque (1943)

- Flesh and Fantasy (1943)

- Double Indemnity (1944)

- Hollywood Canteen (1944)

- Christmas in Connecticut (1945)

- My Reputation (1946)

- The Bride Wore Boots (1946)

- The Strange Love of Martha Ivers (1946)

- California (1947)

- The Two Mrs. Carrolls (1947)

- The Other Love (1947)

- Cry Wolf (1947)

- Variety Girl (1947)

- B.F.’s Daughter (1948)

- Sorry, Wrong Number (1948)

- The Lady Gambles (1949)

- East Side, West Side (1949)

- The File on Thelma Jordon (1950)

- No Man of Her Own (1950)

- The Furies (1950)

- To Please a Lady (1950)

- The Man with a Cloak (1951)

- Clash by Night (1952)

- Jeopardy (1953)

- Titanic (1953)

- All I Desire (1953)

- The Moonlighter (1953)

- Blowing Wild (1953)

- Witness to Murder (1954)

- Executive Suite (1954)

- Cattle Queen of Montana (1954)

- The Violent Men (1955)

- Escape to Burma (1955)

- There’s Always Tomorrow (1956)

- The Maverick Queen (1956)

- These Wilder Years (1956)

- Crime of Passion (1957)

- Trooper Hook (1957)

- Forty Guns (1957)

- Walk on the Wild Side (1962)

- Roustabout (1964)

- The Night Walker (1964)[72][73]

- Calhoun: County Agent (unaired 1964 TV movie)

- The House That Would Not Die (1970 TV movie)

- A Taste of Evil (1971 TV movie)

- The Letters (1973 TV movie)

Radio appearances

- 1952: Hollywood Sound Stage; Dark Victory[74]

- 1952: Theatre Guild on the Air; Portrait in Black[74]

Barbara Stanwyck in Lady of Burlesque (1943)

Awards and nominations

| Year | Association | Category | Work | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1938 | Academy Awards | Best Actress in a Leading Role | Stella Dallas | Nominated | [75] |

| 1942 | Academy Awards | Best Actress in a Leading Role | Ball of Fire | Nominated | [75] |

| 1945 | Academy Awards | Best Actress in a Leading Role | Double Indemnity | Nominated | [75] |

| 1949 | Academy Awards | Best Actress in a Leading Role | Sorry, Wrong Number | Nominated | [75] |

| 1960 | Hollywood Walk of Fame | Motion Pictures, 1751 Vine Street | Won | [76] | |

| 1961 | Emmy Awards | Outstanding Performance by an Actress in a Series | The Barbara Stanwyck Show | Won | [77] |

| 1966 | Emmy Awards | Outstanding Continued Performance by an Actress in a Leading Role | The Big Valley | Won | [77] |

| 1966 | Golden Globe Awards | Best TV Star – Female | The Big Valley | Nominated | [78] |

| 1967 | Emmy Awards | Outstanding Continued Performance by an Actress in a Leading Role | The Big Valley | Nominated | [77] |

| 1967 | Golden Globe Awards | Best TV Star – Female | The Big Valley | Nominated | [78] |

| 1967 | Screen Actors Guild | Life Achievement | Won | [79] | |

| 1968 | Emmy Awards | Outstanding Continued Performance by an Actress in a Leading Role | The Big Valley | Nominated | [77] |

| 1968 | Golden Globe Awards | Best TV Star – Female | The Big Valley | Nominated | [78] |

| 1973 | Hall of Great Western Performers | Won | [80] | ||

| 1981 | Film Society of Lincoln Center Gala Tribute | Won | [75] | ||

| 1981 | Los Angeles Film Critics Association | Career Achievement | Won | [81] | |

| 1982 | Academy Awards | Honorary Award | Won | [81] | |

| 1983 | Emmy Awards | Outstanding Lead Actress in a Limited Series | The Thorn Birds | Won | [81] |

| 1984 | Golden Globe Awards | Best Performance by an Actress in a Supporting Role | The Thorn Birds | Won | [78] |

| 1986 | Golden Globe Awards | Cecil B. DeMille Award | Won | [78] | |

| 1987 | American Film Institute | Life Achievement | Won | [82] |

Barbara Stanwyck in Lady of Burlesque (1943)

References

Notes

Citations

- Jump up^ “”AFI’s 100 Years…100 Stars.””. Archived from the original on October 20, 2006. Retrieved October 23, 2006. American Film Institute. Retrieved: November 17, 2011.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Madsen 1994, p. 8.

- Jump up^ Callahan 2012, pp. 5–6.

- Jump up^ “Ruby Catherine Stevens “Barbara Stanwyck.” Rootsweb; retrieved April 17, 2012.

- Jump up^ Callahan 2012, p. 6.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Madsen 1994, p. 9.

- Jump up^ Mildred G. Smith New York, New York City Municipal Deaths, 7 May 1931

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Nassour and Snowberger 2000.[page needed]

- ^ Jump up to:a b Madsen 1994, p. 10.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Madsen 1994, p. 12.

- Jump up^ Callahan 2012, p. 222.

- Jump up^ Prono 2008, p. 240.

- Jump up^ Madsen 1994, p. 11.

- Jump up^ Madsen 1994, pp. 11–12.

- Jump up^ Madsen 1994, pp. 12–13.

- Jump up^ Madsen 1994, p. 13.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Callahan 2012, p. 9.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h Prono 2008, p. 241.

- Jump up^ Madsen 1994, pp. 17–18.

- Jump up^ Madsen 1994, p. 21.

- Jump up^ Madsen 1994, p. 22.

- Jump up^ Wayne 2009, p. 17.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Madsen 1994, p. 26.

- Jump up^ Madsen 1994, p. 25.

- Jump up^ Smith 1985, p. 8.

- Jump up^ Hopkins 1937[page needed]

- Jump up^ “Barbara Stanwyck.” Arabella-and-co.com. Retrieved: June 19, 2012.

- Jump up^ Wayne 2009, p. 20.

- Jump up^ “Overview: ‘The Other Love’ (1947).” Turner Classic movies.. Retrieved: October 27, 2014.

- Jump up^ Beifuss, John. “A Century of Stanwyck.” Archived June 15, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. The Commercial Appeal (Memphis, Tennessee), July 16, 2007.

- Jump up^ Kael, Pauline. “Quotation of review of the film Ladies of Leisure.” 5001 Nights At The Movies, 1991, p. 403.

- Jump up^ Hannsberry 2009, p. 3.

- Jump up^ Eyman, Scott. “The Lady Stanwyck”. The Palm Beach Post (Florida), July 15, 2007, p. 1J. Retrieved via Access World News: June 16, 2009.

- Jump up^ “Barbara Stanwyck: Forty Guns”. TCM.com. Retrieved November 22, 2016.

- Jump up^ “Hollywood Stuntmen’s Hall of Fame”. stuntmen.org. Retrieved 7 April 2017.

- Jump up^ Capua 2009, p. 165.

- Jump up^ Madsen 1994, p. 32.

- Jump up^ Wilson 2013, p. 51.

- Jump up^ Wayne 2009, p. 37.

- Jump up^ Callahan 2012, pp. 36, 38.

- Jump up^ Prono 2008, p. 242.

- Jump up^ Callahan 2012, p. 85.

- Jump up^ Corliss, Richard. “That Old Feelin’: Ruby in the Rough.” Time magazine, August 12, 2001.

- Jump up^ Callahan 2012, p. 75.

- Jump up^ Wayne 2009, p. 76.

- Jump up^ “The 10 most expensive homes in the US: 2005.” Forbes (2005); retrieved November 17, 2011.

- Jump up^ Wayne 2009, p. 87.

- Jump up^ Callahan 2012, pp. 87, 164.

- Jump up^ Callahan 2012, p. 77.

- Jump up^ Wayne 2009, pp. 146, 166.

- Jump up^ Wagner and Eyman 2008, p. 64.

- Jump up^ King, Susan. “Wagner Memoir Tells of Wood Death, Stanwyck Affair.” San Jose Mercury News (California) October 5, 2008, p. 6D. Retrieved: via Access World News: June 16, 2009.

- Jump up^ Granger and Calhoun 2007, p. 131.

- Jump up^ Callahan 2012, p. 163.

- Jump up^ Wayne 2009, p. 166.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Wilson 2013, p. 266.

- Jump up^ Ross 2011, p. 108.

- Jump up^ Wilson 2013, p. 858.

- Jump up^ Frost 2011, p. 127.

- Jump up^ Diorio 1984, p. 202.

- Jump up^ Barbara Stanwyck biography, imdb.com; retrieved November 17, 2011.

- Jump up^ Metzger 1989, p. 27.

- Jump up^ Peikoff 1997, pp. 403, 497.

- Jump up^ Wilson 2013, p. 23.

- Jump up^ Wilson 2013, p. 123.

- Jump up^ Bert L. Stevens on IMDb

- Jump up^ Stark, John (November 25, 1985). “Ball of Fire: Barbara Stanwyck”. People. Retrieved November 22, 2016.

- Jump up^ Stark, John (February 5, 1990). “Barbara Stanwyck, ‘A Stand-Up Dame'”. People.com. Retrieved December 24, 2010.

- Jump up^ Flint, Peter B. (January 22, 1990). “Barbara Stanwyck, Actress, Dead at 82”. The New York Times. p. D11. Retrieved November 22, 2016.

- Jump up^ Callahan (2012), p. 220.

- Jump up^ Wilson, Scott. Resting Places: The Burial Sites of More Than 14,000 Famous Persons, 3d ed.: 2 (Kindle Location 44716). McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers. Kindle Edition

- Jump up^ “Barbara Stanwyck Filmography.” American Film Institute. Retrieved: August 14, 2014.

- Jump up^ Wilson 2013, pp. 869–887.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Kirby, Walter. “Better Radio Programs for the Week.” The Decatur Daily Review (via Newspapers.com), March 2, 1952, p. 42. Retrieved: May 28, 2015.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e “Barbara Stanwyck Awards.” The New York Times. Retrieved: August 15, 2014.

- Jump up^ “Barbara Stanwyck.” Hollywood Walk of Fame. Retrieved: August 15, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d “Barbara Stanwyck Awards.” Classic Movie People. Retrieved: August 15, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e “Barbara Stanwyck.” Golden Globes. Retrieved: August 15, 2014.

- Jump up^ “4th Life Achievement Recipient, 1966 .” Screen Actors Guild Awards. Retrieved: August 15, 2014.

- Jump up^ “Great Western Performers.” National Cowboy Museum. Retrieved: August 15, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c “Barbara Stanwyck Awards.” AllMovie. Retrieved: August 15, 2014.

- Jump up^ “15th AFI Life Achievement Award.” American Film Institute. Retrieved: August 15, 2014.

Bibliography

- Bachardy, Don. Stars in My Eyes. Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press, 2000. ISBN0-299-16730-5.

- Balio, Tino. Grand design: Hollywood as a Modern Business Enterprise, 1930–1939. Berkeley, California: University of California Press, 1995. ISBN0-520-20334-8.

- Bosworth, Patricia. Jane Fonda: The Private Life of a Public Woman. New York: Houghton, Mifflin, Harcourt, 2011. ISBN978-0-547-15257-8.

- Callahan, Dan. Barbara Stanwyck: The Miracle Woman. Jackson, Mississippi: University Press of Mississippi, 2012. ISBN978-1-61703-183-0.

- Capua, Michelangelo. William Holden: A Biography. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland Press, 2010. ISBN978-0-7864-4440-3.

- Carman, Emily (2015). Independent Stardom: Freelance Women in the Hollywood Studio System. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-1477307816.

- Chierichetti, David and Edith Head. Edith Head: The Life and Times of Hollywood’s Celebrated Costume Designer. New York: HarperCollins, 2003. ISBN0-06-056740-6.

- Diorio, Al. Barbara Stanwyck: A Biography. New York: Coward, McCann, 1984. ISBN978-0-698-11247-6.

- Frost, Jennifer. Hedda Hopper’s Hollywood: Celebrity Gossip and American Conservatism. New York: NYU Press, 2011. ISBN978-0-81472-823-9.

- Granger, Farley and Robert Calhoun. Include Me Out: My Life from Goldwyn to Broadway. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2007. ISBN978-0-312-35773-3.

- Hall, Dennis. American Icons: An Encyclopedia of the People, Places, and Things that have Shaped our Culture. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group, 2006. ISBN0-275-98429-X.

- Hannsberry, Karen Burroughs. Femme Noir: Bad Girls of Film. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland Press, 2009. ISBN978-0-7864-4682-7.

- Hirsch, Foster. The Dark Side of the Screen: Film Noir. New York: Da Capo Press, 2008. ISBN0-306-81772-1.

- Hopkins, Arthur. To a Lonely Boy. New York: Doubleday, Doran & Co., First edition 1937.

- Kael, Pauline. 5001 Nights At The Movies. New York: Henry Holt, 1991. ISBN978-0-8050-1367-2.

- Lesser, Wendy. His Other Half: Men Looking at Women Through Art. Boston: Harvard University Press, 1992. ISBN0-674-39211-6.

- Madsen, Axel. Stanwyck: A Biography. New York: HarperCollins, 1994. ISBN0-06-017997-X.

- Metzger, Robert P. Reagan: American Icon. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1989. ISBN978-0-8122-1302-7.

- Muller, Eddie. Dark City: The Lost World of Film Noir. New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, 1998. ISBN0-312-18076-4.

- Nassour, Ellis and Beth A. Snowberger. “Stanwyck, Barbara”. American National Biography Online (subscription only), February 2000. Retrieved: July 1, 2009.

- Peikoff, Leonard. Letters of Ayn Rand. New York: Plume, 1997. ISBN978-0-452-27404-4.

- “The Rumble: An Off-the-Ball Look at Your Favorite Sports Celebrities.”New York Post, December 31, 2006. Retrieved: June 16, 2009.

- Ross, Steven J. Hollywood Left and Right: How Movie Stars Shaped American Politics. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2011. ISBN978-0-19997-553-2.

- Schackel, Sandra. “Barbara Stanwyck: Uncommon Heroine.” Back in the Saddle: Essays on Western Film and Television Actors. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland Publishing, 1998. ISBN0-7864-0566-X.

- Smith, Ella. Starring Miss Barbara Stanwyck. New York: Random House, 1985. ISBN978-0-517-55695-5.

- Thomson, David. Gary Cooper (Great Stars). New York: Faber & Faber, 2010. ISBN978-0-86547-932-6.

- Wagner, Robert and Scott Eyman. Pieces of My Heart: A Life. New York: HarperEntertainment, 2008. ISBN978-0-06-137331-2.

- Wayne, Jane. Life and Loves of Barbara Stanwyck. London: JR Books Ltd, 2009. ISBN978-1-906217-94-5.

- Wilson, Victoria. A Life of Barbara Stanwyck: Steel-True 1907–1940. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2013. ISBN978-0-684-83168-8.

You must be logged in to post a comment.