Prepared by Daniel B Miller

Harold Clayton Lloyd Sr. (April 20, 1893 – March 8, 1971) was an American actor, comedian, director, producer, screenwriter, and stunt performer who is best known for his silent comedy films.[1]

Lloyd ranks alongside Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton as one of the most popular and influential film comedians of the silent film era. Lloyd made nearly 200 comedy films, both silent and “talkies“, between 1914 and 1947. He is best known for his bespectacled “Glasses” character,[2][3] a resourceful, success-seeking go-getter who was perfectly in tune with 1920s-era United States.

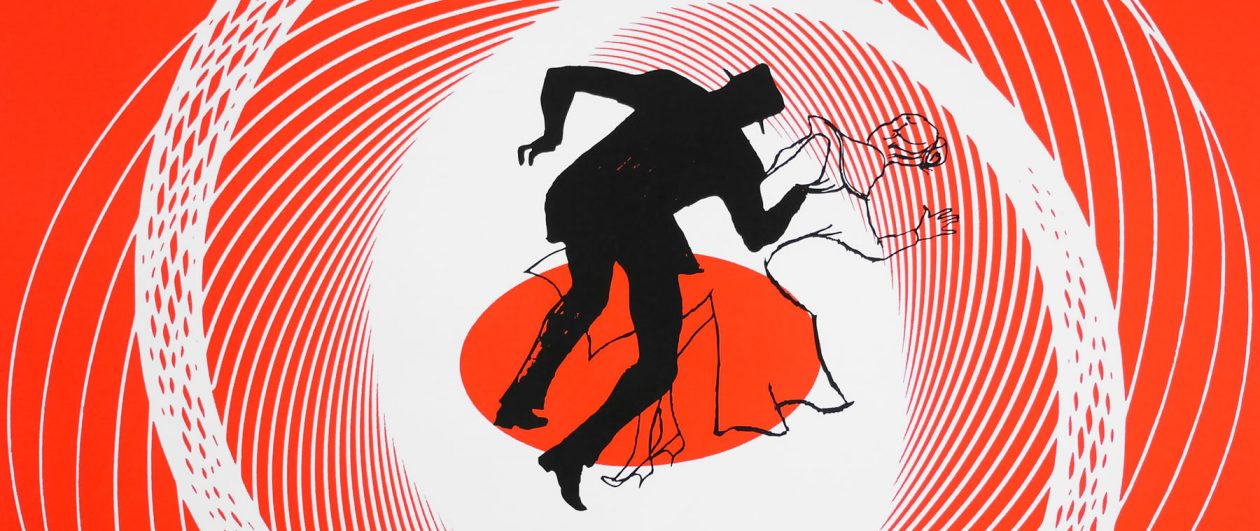

His films frequently contained “thrill sequences” of extended chase scenes and daredevil physical feats, for which he is best remembered today. Lloyd hanging from the hands of a clock high above the street (in reality a trick shot) in Safety Last! (1923) is one of the most enduring images in all of cinema.[4]

Lloyd did many dangerous stunts himself, despite having injured himself in August 1919 while doing publicity pictures for the Roach studio. An accident with a bomb mistaken as a prop resulted in the loss of the thumb and index finger of his right hand[5] (the injury was disguised on future films with the use of a special prosthetic glove, though the glove often did not go unnoticed).

Although Lloyd’s individual films were not as commercially successful as Chaplin’s on average, he was far more prolific (releasing 12 feature films in the 1920s while Chaplin released just four), and made more money overall ($15.7 million to Chaplin’s $10.5 million).[citation needed]

Contents

[hide]

Early life

Harold Clayton Lloyd was born on April 20, 1893 in Burchard, Nebraska, the son of James Darsie Lloyd and Sarah Elisabeth Fraser. His paternal great-grandparents were Welsh.[6]

In 1910, after his father had several business ventures fail, Lloyd’s parents divorced and his father moved with his son to San Diego, California. Lloyd had acted in theater since a child, but in California he began acting in one-reel film comedies around 1912.

Young Harold Lloyd

Career

Silent shorts and features

Lloyd worked with Thomas Edison‘s motion picture company, and his first role was a small part as a Yaqui Indian in the production of The Old Monk’s Tale.

Harold Lloyd in The Old Monk’s Tale (J.Searle Dawley, 1913)

At the age of 20, Lloyd moved to Los Angeles, and took up roles in several Keystone comedies. He was also hired by Universal Studios as an extra and soon became friends with aspiring filmmaker Hal Roach.[7]

Lloyd began collaborating with Roach who had formed his own studio in 1913. Roach and Lloyd created “Lonesome Luke”, similar to and playing off the success of Charlie Chaplin films.[8]

Hal Roach

Harold Lloyd as Lonesome Luke

Harold Lloyd as Lonesome Luke

Harold Lloyd as Lonesome Luke

Lloyd hired Bebe Daniels as a supporting actress in 1914; the two of them were involved romantically and were known as “The Boy” and “The Girl”. In 1919, she left Lloyd to pursue her dramatic aspirations. Later that year, Lloyd replaced Daniels with Mildred Davis, whom he would later marry. Lloyd was tipped off by Hal Roach to watch Davis in a movie. Reportedly, the more Lloyd watched Davis the more he liked her. Lloyd’s first reaction in seeing her was that “she looked like a big French doll”.[9]

Bebe Daniels

Bebe Daniels

Bebe Daniels

Harold Lloyd and Bebe Daniels in Look Pleasant, Please (Alfred J Goulding, 1918)

The Rolin Film Company – 1915

Bebe Daniels (1rst row, middle), Harold Lloyd (2nd Row, middle – in Lonesome Luke costume), Snub Pollard to his left, Hal Roach (3rd row, middle)

Harold Lloyd and Bebe Daniels

By 1918, Lloyd and Roach had begun to develop his character beyond an imitation of his contemporaries. Harold Lloyd would move away from tragicomic personas, and portray an everyman with unwavering confidence and optimism.

The persona Lloyd referred to as his “Glass” character[10] (often named “Harold” in the silent films) was a much more mature comedy character with greater potential for sympathy and emotional depth, and was easy for audiences of the time to identify with.

The “Glass” character is said to have been created after Roach suggested that Harold was too handsome to do comedy without some sort of disguise. To create his new character Lloyd donned a pair of lensless horn-rimmed eyeglasses but wore normal clothing;[3] previously, he had worn a fake mustache and ill-fitting clothes as the Chaplinesque “Lonesome Luke”.

Harold Lloyd – The Glass Character

“When I adopted the glasses,” he recalled in a 1962 interview with Harry Reasoner, “it more or less put me in a different category because I became a human being. He was a kid that you would meet next door, across the street, but at the same time I could still do all the crazy things that we did before, but you believed them. They were natural and the romance could be believable.”

Unlike most silent comedy personae, “Harold” was never typecast to a social class, but he was always striving for success and recognition. Within the first few years of the character’s debut, he had portrayed social ranks ranging from a starving vagrant in From Hand to Mouth to a wealthy socialite in Captain Kidd’s Kids.

Harold Lloyd and Peggy Cartwright in From Hand to Mouth (Alfred J Goulding, Hal Roach, 1919)

Poster for Captain Kidd’s Kids (Hal Roach, 1919)

Lloyd’s career was not all laughs, however. In August 1919, while filming Haunted Spooks (Alfred J Goulding, Hal Roach, 1919) posing for some promotional still photographs in the Los Angeles Witzel Photography Studio, he was seriously injured holding a prop bomb thought merely to be a smoke pot.

It exploded and mangled his hand, causing him to lose a thumb and forefinger. The blast was severe enough that the cameraman and prop director nearby were also seriously injured.

Harold Lloyd and Mildred Davis in Haunted Spooks (Alfred J Goulding, Hal Roach, 1919)

Lloyd was in the act of lighting a cigarette from the fuse of the bomb when it exploded, also badly burning his face and chest and injuring his eye. Despite the proximity of the blast to his face, he retained his sight. As he recalled in 1930, “I thought I would surely be so disabled that I would never be able to work again. I didn’t suppose that I would have one five-hundredth of what I have now. Still I thought, ‘Life is worth while. Just to be alive.’ I still think so.”[11]

Beginning in 1921, Roach and Lloyd moved from shorts to feature-length comedies. These included the acclaimed Grandma’s Boy, which (along with Chaplin’s The Kid) pioneered the combination of complex character development and film comedy, the highly popular Safety Last!(1923), which cemented Lloyd’s stardom (and is the oldest film on the American Film Institute‘s List of 100 Most Thrilling Movies), and Why Worry? (1923).

Poster for Grandma’s Boy (Fred C Newmayer, 1922)

Harold Lloyd and Dick Sutherland in Grandma’s Boy (Fred C Newmayer, 1922)

Poster for Safety Last (Fred C Newmeyer, 1923)

Harold Lloyd in Safety Last (Fred C Newmeyer, 1923)

Harold Lloyd in Why Worry? (Fred C Newmeyer, 1923)

Harold Lloyd in Why Worry? (Fred C Newmeyer, 1923)

Lloyd and Roach parted ways in 1924, and Lloyd became the independent producer of his own films.

These included his most accomplished mature features Girl Shy, The Freshman (his highest-grossing silent feature), The Kid Brother, and Speedy, his final silent film. Welcome Danger (1929) was originally a silent film but Lloyd decided late in the production to remake it with dialogue.

All of these films were enormously successful and profitable, and Lloyd would eventually become the highest paid film performer of the 1920s.[12] They were also highly influential and still find many fans among modern audiences, a testament to the originality and film-making skill of Lloyd and his collaborators. From this success, he became one of the wealthiest and most influential figures in early Hollywood.

Harold Lloyd and Jobyna Ralston (Fred C Newmeyer, 1924)

Harold Lloyd and Jobyna Ralston (Fred C Newmeyer, 1924)

Poster for The Freshman (Fred C Newmeyer, 1925)

Harold Lloyd in The Freshman (Fred C Newmeyer, 1925)

Poster for The Kid Brother (Ted Wilde, Harold Lloyd, 1927)

Harold Lloyd and Jobyna Ralston in The Kid Brother (Ted Wilde, Harold Lloyd, 1927)

Lobby card for Speedy (Ted Wilde, 1928)

Harold Lloyd and Ann Christy in Speedy (Ted Wilde, 1928)

Poster for Welcome Danger (Clyde Bruckman, Malcolm St.Clair, 1929)

Harold Lloyd and Barbara Kent on the set of Welcome Danger (Clyde Bruckman, Malcolm St.Clair, 1929)

Talkies and transition

In 1924, Lloyd formed his own independent film production company, the Harold Lloyd Film Corporation, with his films distributed by Pathé and later Paramount and Twentieth Century-Fox. Lloyd was a founding member of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

Released a few weeks before the start of the Great Depression, Welcome Danger was a huge financial success, with audiences eager to hear Lloyd’s voice on film. Lloyd’s rate of film releases, which had been one or two a year in the 1920s, slowed to about one every two years until 1938.

Promotional poster for Welcome Danger (Clyde Bruckman, Malcolm St.Clair, 1929)

The films released during this period were: Feet First, with a similar scenario to Safety Last which found him clinging to a skyscraper at the climax; Movie Crazy with Constance Cummings; The Cat’s-Paw, which was a dark political comedy and a big departure for Lloyd; and The Milky Way, which was Lloyd’s only attempt at the fashionable genre of the screwball comedy film.

Lobby card for Feet First (Clyde Bruckman, Harold Lloyd, 1930)

Poster for Movie Crazy (Clyde Bruckman, Harold Lloyd, 1932)

Lobby card for The Cat’s Paw (Sam Taylor, Harold Lloyd, 1934)

Lobby card for The Milky Way (Leo McCarey, Ray McCarey, 1936)

To this point the films had been produced by Lloyd’s company. However, his go-getting screen character was out of touch with Great Depression movie audiences of the 1930s. As the length of time between his film releases increased, his popularity declined, as did the fortunes of his production company. His final film of the decade, Professor Beware, was made by the Paramount staff, with Lloyd functioning only as actor and partial financier.

Lobby card for Professor Beware (Elliott Nugent, 1938)

On March 23, 1937, Lloyd sold the land of his studio, Harold Lloyd Motion Picture Company, to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. The location is now the site of the Los Angeles California Temple.[13]

Lloyd produced a few comedies for RKO Radio Pictures in the early 1940s but otherwise retired from the screen until 1947. He returned for an additional starring appearance in The Sin of Harold Diddlebock, an ill-fated homage to Lloyd’s career, directed by Preston Sturges and financed by Howard Hughes.

Lobby card for The Sin of Harold Diddlebock AKA Mad Wednesday (Preston Sturges, 1947)

This film had the inspired idea of following Harold’s Jazz Age, optimistic character from The Freshman into the Great Depression years. Diddlebock opened with footage from The Freshman (for which Lloyd was paid a royalty of $50,000, matching his actor’s fee) and Lloyd was sufficiently youthful-looking to match the older scenes quite well.

Lloyd and Sturges had different conceptions of the material and fought frequently during the shoot; Lloyd was particularly concerned that while Sturges had spent three to four months on the script of the first third of the film, “the last two thirds of it he wrote in a week or less”.

The finished film was released briefly in 1947, then shelved by producer Hughes. Hughes issued a recut version of the film in 1951 through RKO under the title Mad Wednesday. Such was Lloyd’s disdain that he sued Howard Hughes, the California Corporation and RKO for damages to his reputation “as an outstanding motion picture star and personality”, eventually accepting a $30,000 settlement.

German poster for The Sin of Harold Diddlebock AKA Mad Wednesday (Preston Sturges, 1947)

Radio and retirement

In October 1944, Lloyd emerged as the director and host of The Old Gold Comedy Theater, an NBC radio anthology series, after Preston Sturges, who had turned the job down, recommended him for it. The show presented half-hour radio adaptations of recently successful film comedies, beginning with Palm Beach Story with Claudette Colbert and Robert Young.

Rehearsing the script for “The Palm Beach Story” are Robert Young, Harold Lloyd and Claudette Colbert – The Old Gold Comedy Theatre

Some saw The Old Gold Comedy Theater as being a lighter version of Lux Radio Theater, and it featured some of the best-known film and radio personalities of the day, including Fred Allen, June Allyson, Lucille Ball, Ralph Bellamy, Linda Darnell, Susan Hayward, Herbert Marshall, Dick Powell, Edward G. Robinson, Jane Wyman, and Alan Young.

But the show’s half-hour format—which meant the material might have been truncated too severely—and Lloyd’s sounding somewhat ill at ease on the air for much of the season (though he spent weeks training himself to speak on radio prior to the show’s premiere, and seemed more relaxed toward the end of the series run) may have worked against it.

The Old Gold Comedy Theater ended in June 1945 with an adaptation of Tom, Dick and Harry, featuring June Allyson and Reginald Gardiner and was not renewed for the following season. Many years later, acetate discs of 29 of the shows were discovered in Lloyd’s home, and they now circulate among old-time radio collectors.

Harold Lloyd and Dick Powell – The Old Gold Comedy Theatre

Lloyd remained involved in a number of other interests, including civic and charity work. Inspired by having overcome his own serious injuries and burns, he was very active as a Freemason and Shriner with the Shriners Hospital for Crippled Children.

He was a Past Potentate of Al-Malaikah Shrine in Los Angeles, and was eventually selected as Imperial Potentate of the Shriners of North America for the year 1949–50.[14] At the installation ceremony for this position on July 25, 1949, 90,000 people were present at Soldier Field, including then sitting U.S. President Harry S Truman, also a 33° Scottish Rite Mason.[15] In recognition of his services to the nation and Freemasonry, Bro. Lloyd was invested with the Rank and Decoration of Knight Commander Court of Honour in 1955 and coroneted an Inspector General Honorary, 33°, in 1965.

Harold Lloyd in 1946, when he was appointed to the Shriners’ publicity committee

He appeared as himself on several television shows during his retirement, first on Ed Sullivan‘s variety show Toast of the Town June 5, 1949, and again on July 6, 1958. He appeared as the Mystery Guest on What’s My Line? on April 26, 1953, and twice on This Is Your Life: on March 10, 1954 for Mack Sennett, and again on December 14, 1955, on his own episode. During both appearances, Lloyd’s hand injury can clearly be seen.[16]

Harold Lloyd on This is Your Life in 1950’s

Lloyd studied colors and microscopy, and was very involved with photography, including 3D photography and color film experiments. Some of the earliest 2-color Technicolor tests were shot at his Beverly Hills home (These are included as extra material in the Harold Lloyd Comedy Collection DVD Box Set).

Harold Lloyd’s 3 D Photography Album

He became known for his nude photographs of models, such as Bettie Page and stripper Dixie Evans, for a number of men’s magazines. He also took photos of Marilyn Monroe lounging at his pool in a bathing suit, which were published after her death. In 2004, his granddaughter Suzanne produced a book of selections from his photographs, Harold Lloyd’s Hollywood Nudes in 3D! (ISBN 1-57912-394-5).

Harold Lloyd’s 3 D Photography Album

Lloyd also provided encouragement and support for a number of younger actors, such as Debbie Reynolds, Robert Wagner, and particularly Jack Lemmon, whom Harold declared as his own choice to play him in a movie of his life and work.

Marilyn Monroe photographed by Harold Lloyd

Marilyn Monroe photographed by Harold Lloyd during a photo session with Philippe Halsman, 1952

Marilyn Monroe photographed by Harold Lloyd

Renewed interest

Lloyd kept copyright control of most of his films and re-released them infrequently after his retirement.

Lloyd did not grant cinematic release because most theaters could not accommodate an organist, and Lloyd did not wish his work to be accompanied by a pianist: “I just don’t like pictures played with pianos.

We never intended them to be played with pianos.” Similarly, his features were never shown on television as Lloyd’s price was high: “I want $300,000 per picture for two showings. That’s a high price, but if I don’t get it, I’m not going to show it. They’ve come close to it, but they haven’t come all the way up”.

As a consequence, his reputation and public recognition suffered in comparison with Chaplin and Keaton, whose work has generally been more available. Lloyd’s film character was so intimately associated with the 1920s era that attempts at revivals in 1940s and 1950s were poorly received, when audiences viewed the 1920s (and silent film in particular) as old-fashioned.

Harold Lloyd and Mildred Davis in 1935

In the early 1960s, Lloyd produced two compilation films, featuring scenes from his old comedies, Harold Lloyd’s World of Comedy and The Funny Side of Life.

The first film was premiered at the 1962 Cannes Film Festival, where Lloyd was fêted as a major rediscovery. The renewed interest in Lloyd helped restore his status among film historians.

Throughout his later years he screened his films for audiences at special charity and educational events, to great acclaim, and found a particularly receptive audience among college audiences: “Their whole response was tremendous because they didn’t miss a gag; anything that was even a little subtle, they got it right away.”

Lobby cards for Harold Lloyd’s World of Comedy (Harold Lloyd, 1962)

Poster for The Funny Side of Life (Harry Kerwin, 1963)

Following his death, and after extensive negotiations, most of his feature films were leased to Time-Life Films in 1974.

As Tom Dardis confirms: “Time-Life prepared horrendously edited musical-sound-track versions of the silent films, which are intended to be shown on TV at sound speed [24 frames per second], and which represent everything that Harold feared would happen to his best films”.[citation needed]

Time-Life released the films as half-hour television shows, with two clips per show. These were often near-complete versions of the early two-reelers, but also included extended sequences from features such as Safety Last! (terminating at the clock sequence) and Feet First (presented silent, but with Walter Scharf‘s score from Lloyd’s own 1960s re-release).

Belgian poster for Safety Last (Fred C Newmeyer, Sam Taylor, 1923)

Time-Life released several of the feature films more or less intact, also using some of Scharf’s scores which had been commissioned by Lloyd. The Time-Life clips series included a narrator rather than intertitles. Various narrators were used internationally: the English-language series was narrated by Henry Corden.

The Time-Life series was frequently repeated by the BBC in the United Kingdom during the 1980s, and in 1990 a Thames Television documentary, Harold Lloyd: The Third Genius was produced by Kevin Brownlow and David Gill, following two similar series based on Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton.[17] Composer Carl Davis wrote a new score for Safety Last! which he performed live during a showing of the film with the Royal Scottish National Orchestra to great acclaim in 1993.[18]

Harold Lloyd, The Third Genius (Kevin Brownlow, David Gill, 1990)

Harold Lloyd, The Third Genius (Kevin Brownlow, David Gill, 1990) – VHS Release

The Brownlow and Gill documentary was shown as part of the PBS series American Masters, and created a renewed interest in Lloyd’s work in the United States, but the films were largely unavailable.

In 2002, the Harold Lloyd Trust re-launched Harold Lloyd with the publication of the book Harold Lloyd: Master Comedian by Jeffrey Vance and Suzanne Lloyd[19][20] and a series of feature films and short subjects called “The Harold Lloyd Classic Comedies” produced by Jeffrey Vance and executive produced by Suzanne Lloyd for Harold Lloyd Entertainment.

The new cable television and home video versions of Lloyd’s great silent features and many shorts were remastered with new orchestral scores by Robert Israel. These versions are frequently shown on the Turner Classic Movies(TCM) cable channel.

A DVD collection of these restored or remastered versions of his feature films and important short subjects was released by New Line Cinema in partnership with the Harold Lloyd Trust in 2005, along with theatrical screenings in the US, Canada, and Europe. Criterion Collection has subsequently acquired the home video rights to the Lloyd library, and have released Safety Last!,[21] The Freshman,[22] and Speedy.[23]

Safety Last – Criterion Collection Blu Ray Special Edition

The Freshman – Criterion Collection – Dual Format Edition

The Freshman – Criterion Collection – Blu Ray Special Edition

In the June 2006 Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra Silent Film Gala program book for Safety Last!, film historian Jeffrey Vance stated that Robert A. Golden, Lloyd’s assistant director, routinely doubled for Harold Lloyd between 1921 and 1927. According to Vance, Golden doubled Lloyd in the bit with Harold shimmy shaking off the building’s ledge after a mouse crawls up his trousers.[24]

Harold Lloyd Comedy Collection – DVD Release

Personal life

They had two children together: Gloria Lloyd (1923-2012)[26][27] and Harold Clayton Lloyd Jr. (1931–1971).[28] They also adopted Gloria Freeman (1924—1986) in September 1930, whom they renamed Marjorie Elizabeth Lloyd but was known as “Peggy” for most of her life.

Lloyd discouraged Davis from continuing her acting career. He later relented but by that time her career momentum was lost. Davis died from a heart attack in 1969, two years before Lloyd’s death.

Though her real age was a guarded secret, a family spokesperson at the time indicated she was 66 years old. Lloyd’s son was gay and, according to Annette D’Agostino Lloyd (no relation) in the book Harold Lloyd: Master Comedian, Harold Sr. took this in good spirit. Harold Jr. died from complications of a stroke three months after his father.

Harold Lloyd and Mildred Davis

The Lloyds in 1936. From left to right: Peggy and Harold Jr., Harold, Gloria, and Mildred

In 1925, at the height of his movie career, Lloyd entered into Freemasonry at the Alexander Hamilton Lodge No. 535 of Hollywood, advancing quickly through both the York Rite and Scottish Rite, and then joined Al Malaikah Shrine in Los Angeles. He took the degrees of the Royal Arch with his father. In 1926, he became a 32° Scottish Rite Mason in the Valley of Los Angeles, California. He was vested with the Rank and Decoration of Knight Commander Court of Honor (KCCH) and eventually with the Inspector General Honorary, 33rd degree.

Harold Lloyd and Freemasons

Harold Lloyd at Al Malaikah Shrine in Los Angeles

Lloyd’s Beverly Hills home, “Greenacres“, was built in 1926–1929, with 44 rooms, 26 bathrooms, 12 fountains, 12 gardens, and a nine-hole golf course. A portion of Lloyd’s personal inventory of his silent films (then estimated to be worth $2 million) was destroyed in August 1943 when his film vault caught fire. Seven firemen were overcome while inhaling chlorine gas from the blaze.

Lloyd himself was saved by his wife, who dragged him to safety outdoors after he collapsed at the door of the film vault. The fire spared the main house and outbuildings. After attempting to maintain the home as a museum of film history, as Lloyd had wished, the Lloyd family sold it to a developer in 1975.

Harold Lloyd house fire

Harold Lloyd Estate

The grounds were subsequently subdivided but the main house and the estate’s principal gardens remain and are frequently used for civic fundraising events and as a filming location, appearing in films like Westworld and The Loved One. It is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Greenacres was built in the 1920s in Beverly Hills, one of Los Angeles’ all-white planned communities.[29] The area had restrictive covenants prohibiting non-whites (this also included Jews[30]) from living there unless they were in the employment of a white resident (typically as a domestic servant).[31]:57

In 1940, Lloyd supported a neighborhood improvement association in Beverly Hills that attempted to enforce the all-white covenant in court after a number of black actors and businessmen had begun buying properties in the area.

However, in his decision, federal judge Thurmond Clarke dismissed the action stating that it was time that “members of the Negro race are accorded, without reservations or evasions, the full rights guaranteed to them under the 14th amendment.”[32] In 1948 the United States Supreme Court declared in Shelley v. Kraemer that all racially restrictive covenants in the United States were unenforceable.[33]

Death

Lloyd died at age 77 from prostate cancer on March 8, 1971, at his Greenacres home in Beverly Hills, California.[12][34][35]

He was interred in a crypt in the Great Mausoleum at Forest Lawn Memorial Park Cemetery in Glendale, California.[36] His former co-star Bebe Daniels died eight days after him and his son Harold Lloyd Jr.died three months after him.[citation needed]

The crypt of Harold Lloyd, in the Great Mausoleum, Forest Lawn Glendale

Honors

In 1927, his was only the fourth concrete ceremony at Grauman’s Chinese Theatre, preserving his handprints, footprints, and autograph, along with the outline of his famed glasses (which were actually a pair of sunglasses with the lenses removed).[37][38] The ceremony took place directly in front of the Hollywood Masonic Temple, which was the meeting place of the Masonic lodge to which he belonged.[39]

Harold Lloyd hand and foot prints

Lloyd was honoured in 1960 for his contribution to motion pictures with a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame located at 1503 Vine Street.[40] In 1994, he was honoured with his image on a United States postage stamp designed by caricaturist Al Hirschfeld.[41][42]

In 1953, Lloyd received an Academy Honorary Award for being a “master comedian and good citizen”. The second citation was a snub to Chaplin, who at that point had fallen foul of McCarthyism and had his entry visa to the United States revoked. Regardless of the political overtones, Lloyd accepted the award in good spirit.

Filmography

See also

References

- Jump up^ Obituary Variety, March 10, 1971, page 55.

- Jump up^ Austerlitz, Saul (2010). Another Fine Mess: A History of American Film Comedy. Chicago Review Press. p. 28. ISBN 1569767637.

- ^ Jump up to:a b D’Agostino Lloyd, Annette. “Why Harold Lloyd Is Important”. haroldlloyd.com. Retrieved November 12, 2013.

- Jump up^ Slide, Anthony (September 27, 2002). Silent Players: A Biographical and Autobiographical Study of 100 Silent Film Actors and Actresses. Univ. Press of Kentucky. p. 221. ISBN 978-0813122496.

- Jump up^ An American Comedy; Lloyd and Stout; 1928; page 129

- Jump up^ “Comedy in the 1920’s – 1950’s”. alphadragondesign.com. Retrieved April 13,2015.

- Jump up^ “Encyclopedia of the Great Plains – Lloyd, Harold (1893-1971)”. unl.edu. Retrieved April 13, 2015.

- Jump up^ “Hal Roach article”. Silentsaregolden.com. Retrieved 2016-07-21.

- Jump up^ Pawlak, Debra Ann (January 15, 2011). Bringing Up Oscar: The Story of the Men and Women Who Founded the Academy. New York: Pegasus Books. p. 62. ISBN 978-1605981376.

- Jump up^ “Harold Lloyd biography”. haroldlloyd.com. Retrieved November 12, 2013.

- Jump up^ Hall, Gladys (October 1930). “Discoveries About Myself”. Motion Picture Magazine. New York: Brewster Publications. Retrieved October 23, 2015.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Died”. Time. March 22, 1971. Retrieved June 8, 2008.

Harold Lloyd, 77, comedian whose screen image of horn-rimmed incompetence made him Hollywood’s highest-paid star in the 1920s; of cancer; in Hollywood. He usually played a feckless Mr. Average who triumphed over misfortune. ‘My character represented the white-collar middle class that felt frustrated but was always fighting to overcome its shortcomings,’ he once explained. Lloyd usually did his own stunt work, as in Safety Last (1923), in which he dangled from a clock high above the street; he was protected only by a wooden platform two floors below.

- Jump up^ “Los Angeles California Temple”. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Retrieved June 8, 2008.

The land for the Los Angeles California Temple was purchased from Harold Lloyd Motion Picture Company on March 23, 1937.

- Jump up^ “Harold LLoyd” Archived January 22, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. “In 1949, Harold’s face graced the cover of TIME Magazine as the Imperial Potentate of the Ancient Arabic Order of the Nobles of the Mystic Shrine, their highest-ranking position. He devoted an entire year to visiting 130 temples across the country giving speeches for over 700,000 Shriners. The last twenty years of his life he worked tirelessly for the twenty-two Shriner Hospitals for Children and in the 1960s, he was named President and Chairman of the Board.”

- Jump up^ Lloyd, Harold. “Phoenix Masonry Masonic Museum”. Masonic Research. Phoenix Masonry. Retrieved July 29, 2012.

- Jump up^ “Harold Lloyd”. IMDB. Retrieved June 8, 2008.

- Jump up^ Documentary: Harold Lloyd — The Third Genius.

- Jump up^ https://issuu.com/fm_fortissimo/docs/faber_silents_catalogue_2016

- Jump up^ Loos, Ted (2002-07-21). “Books in Brief – Nonfiction – A Matter of Attitude”. New York Times. Retrieved 2016-07-21.

- Jump up^ “Behind the Laughter”. latimes. Retrieved April 13, 2015.

- Jump up^ “Safety Last!”. The Criterion Collection. Retrieved April 13, 2015.

- Jump up^ “The Freshman”. The Criterion Collection. Retrieved April 13, 2015.

- Jump up^ “Speedy”. The Criterion Collection. Retrieved 2017-05-19.

- Jump up^ “”Safety Last!: Notes on the Making of the Film” : Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra Silent Film Gala program book, June 3, 2006 revised and reprinted as “Safety Last!” San Francisco Silent Film Festival program book, July 18–21, 2013″. Silentfilm.org. Retrieved 2016-07-21.

- Jump up^ Los Angeles, California, County Marriages 1850-1952

- Jump up^ “Gloria Lloyd, daughter of Harold Lloyd, dies”. Variety. February 11, 2012. Retrieved 2012-02-11.

- Jump up^ Brownlow, Kevin (27 February 2012). “Obituaries: Gloria Lloyd: Actress who had a gilded life as Harold Lloyd’s daughter”. The Independent. Retrieved 2015-09-30.

- Jump up^ “Harold Lloyd Jr. Dies. Actor, Son of Comedy Star”. The New York Times. June 10, 1971. Retrieved June 8, 2008.

- Jump up^ James W. Loewen (September 29, 2005). Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension Of American Racism. The New Press. p. 112. ISBN 978-1-59558-674-2. Retrieved August 19, 2012.

- Jump up^ Andrew Wiese (December 15, 2005). Places of Their Own: African American Suburbanization in the Twentieth Century. University of Chicago Press. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-226-89625-0. Retrieved August 19, 2012.

- Jump up^ Michael Gross (November 1, 2011). Unreal Estate: Money, Ambition, and the Lust for Land in Los Angeles. Random House Digital, Inc. ISBN 978-0-7679-3265-3. Retrieved August 17, 2012.

- Jump up^ Stephen Grant Meyer (October 1, 2001). As Long As They Don’t Move Next Door: Segregation and Racial Conflict in American Neighborhoods. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 76. ISBN 978-0-8476-9701-4. Retrieved August 19, 2012.

- Jump up^ Steve Sheppard (April 1, 2007). The History of Legal Education in the United States: Commentaries And Primary Sources. The Lawbook Exchange, Ltd. p. 948n. ISBN 978-1-58477-690-1. Retrieved August 19, 2012.

- Jump up^ “Harold Lloyd, Bespectacled Film Comic, Dies of Cancer at 77”. Los Angeles Times. March 9, 1971. Retrieved June 8, 2008.

Comedian Harold Lloyd, 77, who bumbled through more than 300 films as a bespectacled victim of life’s difficulties, died of cancer Monday at his Beverly Hills home.

- Jump up^ Illson, Murray (March 9, 1971). “Horn-Rims His Trademark; Harold Lloyd, Screen Comedian, Dies at 77”. The New York Times. Retrieved June 8, 2008.

A pair of inexpensive, horn-rimmed eyeglass frames without lenses, the shy expression of a somewhat bewildered adolescent and a single-track ambition made Harold Clayton Lloyd the highest-paid screen actor in Hollywood’s golden age of the nineteen twenties.

- Jump up^ Harold Lloyd at Find a Grave

- Jump up^ “Harold Lloyd’s Prints At Mann’s Chinese Theatre”. Getty Images. Retrieved 2017-06-27.

- Jump up^ Bengtson, John (2011-05-21). “Harold Lloyd – lasting impressions at Grauman’s Chinese”. Chaplin-Keaton-Lloyd film locations (and more). Retrieved 2017-06-27.

- Jump up^ Ridenour, Al (2002-05-02). “A Chamber of Secrets”. Los Angeles Times. pp. 1–2. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved 2017-06-27.

- Jump up^ “Harold Lloyd | Hollywood Walk of Fame”. http://www.walkoffame.com. Retrieved 2017-06-27.

- Jump up^ Hirschfeld, Al (2015). The Hirschfeld Century: Portrait of an Artist and His Age. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. pp. 291, 293. ISBN 9781101874974. OCLC 898029267.

- Jump up^ McAllister, Bill (1994-04-15). “Hirschfeld’s ‘Silent’ Stars”. The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2017-06-27.

Further reading

- Agee, James (2000) [1958]. “Comedy’s Greatest Era” from Life magazine (9/5/1949), reprinted in Agee on Film. McDowell, Obolensky, Modern Library.

- Bengtson, John. (2011). Silent Visions: Discovering Early Hollywood and New York Through the Films of Harold Lloyd. Santa Monica Press. ISBN 978-1-59580-057-2.

- Brownlow, Kevin (1976) [1968]. “Harold Lloyd” from The Parade’s Gone By. Alfred A. Knopf, University of California Press.

- Byron, Stuart; Weis, Elizabeth (1977). The National Society of Film Critics on Movie Comedy. Grossman/Viking.

- Cahn, William (1964). Harold Lloyd’s World of Comedy. Duell, Sloane & Pearce.

- D’Agostino, Annette M. (1994). Harold Lloyd: A Bio-Bibliography. Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-28986-7.

- Dale, Alan (2002). Comedy is a Man in Trouble: Slapstick In American Movies. University of Minnesota Press.

- Dardis, Tom (1983). Harold Lloyd: The Man on the Clock. Viking. ISBN 0-14-007555-0.

- Durgnat, Raymond (1970). “Self-Help with a Smile” from The Crazy Mirror: Hollywood Comedy and the American Image. Dell.

- Everson, William K. (1978). American Silent Film. Oxford University Press.

- Gilliatt, Penelope (1973). “Physicists” from Unholy Fools: Wits, Comics, Disturbers of the Peace. Viking.

- Hayes, Suzanne Lloyd (ed.), (1992). 3-D Hollywood with Photography by Harold Lloyd. Simon & Schuster.

- Kerr, Walter (1990) [1975]. The Silent Clowns. Alfred A. Knopf, Da Capo Press.

- Lacourbe, Roland (1970). Harold Lloyd. Paris: Editions Seghers.

- Lahue, Kalton C. (1966). World of Laughter: The Motion Picture Comedy Short, 1910–1930. University of Oklahoma Press.

- Lloyd, Annette D’Agostino (2003). The Harold Lloyd Encyclopedia. McFarland & Company. ISBN 0-7864-1514-2.

- Lloyd, Annette D’Agostino (2009). Harold Lloyd: Magic in a Pair of Horn-Rimmed Glasses. BearManor Media. ISBN 978-1-59393-332-6.

- Lloyd, Harold; Stout, W. W. (1971) [1928]. An American Comedy. Dover.

- Lloyd, Suzanne (2004). Harold Lloyd’s Hollywood Nudes in 3-D. Black Dog & Leventhal. ISBN 978-1-57912-394-9.

- Maltin, Leonard (1978). The Great Movie Comedians. Crown Publishers.

- Mast, Gerald (1979) [1973]. The Comic Mind: Comedy and the Movies. University of Chicago Press.

- McCaffrey, Donald W. (1968). 4 Great Comedians: Chaplin, Lloyd, Keaton, Langdon. A.S. Barnes.

- McCaffrey, Donald W. (1976). Three Classic Silent Screen Comedies Starring Harold Lloyd. Associated University Presses. ISBN 0-8386-1455-8.

- Mitchell, Glenn (2003). A–Z of Silent Film Comedy. B.T. Batsford Ltd.

- Reilly, Adam (1977). Harold Lloyd: The King of Daredevil Comedy. Macmillan. ISBN 0-02-601940-X.

- Robinson, David (1969). The Great Funnies: A History of Film Comedy. E.P. Dutton.

- Schickel, Richard (1974). Harold Lloyd: The Shape of Laughter. New York Graphic Society. ISBN 0-8212-0595-1.

- Vance, Jeffrey; Lloyd, Suzanne (2002). Harold Lloyd: Master Comedian. Harry N Abrams. ISBN 0-8109-1674-6.

William Desmond Hurst

William Desmond Hurst

You must be logged in to post a comment.